A first-person perspective on Jim Crow in 1950s Southern Appalachia — part 1

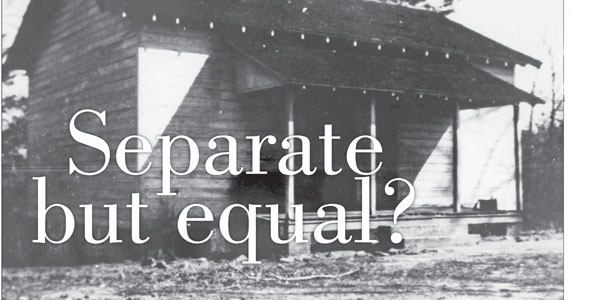

“Separate but equal” facilities such as Soapstone Elementary School in the Pumpkintown area of Pickens County proliferated the South in the first half of the 20th century.

Photo courtesy Pickens County Library System

By Dr. Thomas Cloer, Jr.

Special to the Courier

“Dad, why don’t Mark and Luke just go with us to school? Why do they have to go all the way to the next county?” I asked after a game of basketball where the twin boys showed their moves at the home of Jim and Hazel Wood.

[cointent_lockedcontent]

The year was 1955, and the twin boys of Floyd and Elnora Roberts were two of the first African-American youngsters I ever knew. I had seen them at their church, Pleasant Grove Church, where the Roberts family attended just across the way from the Woods family’s home in the Northcutt Community of Gilmer County, Ga. This is where the little bucolic mountain town of Ellijay is located in the North Georgia Mountains, very near where the Appalachian Mountain Range begins.

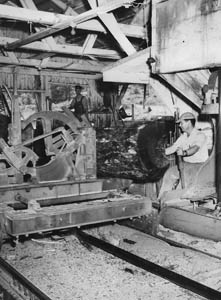

Photo courtesy Dr. Thomas Cloer III Author’s father, Carl T. Cloer Sr., operating a steam-powered log carriage in Turniptown, Ga., in 1951.

We moved to Ellijay, where I began school, in 1951 as my grandfather, dad, uncles and cousins moved with Gennett Lumber Company. My dad, Carl T. Cloer Sr., sawed with a huge band saw on a wheel 8 feet in diameter, traveling a mile per minute and ripping giant hardwood logs on a daredevil, steam-driven log carriage with a “shotgun feed.” After each cut, the explosive return of Dad’s log carriage would result in a loud steam “Boom!” heard throughout the Turniptown Mountains, thus the term “shotgun feed.”

“Tom, I really can’t explain why the Roberts boys can’t go to school here. I’m just a sawmill man, and I don’t run the show. I know their daddy, Floyd Roberts, is as fine a gentleman as I ever met. When I see him, he never fails to ask me to come, bring my family, and go with him to his Pleasant Grove Church. And you know I have taken you there more than once.”

“What do you mean, Dad, by ‘I don’t run the show’?”

“I mean, Tom, I have no power to tell Mark and Luke that they can go to school here. If they did try, there would be problems, because they are of a different race. There are customs and laws that keep them from going to school with you.”

Jim Crow

That was my introduction to Jim Crow in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. The term “Jim Crow” originated in the 1830s, when a white minstrel show performer, Tom Rice, blackened his face with burned cork and danced a silly little jig while singing “Jump Jim Crow.” We may never know who Jim Crow actually was. Some attribute the name to an elderly black man who had difficulty walking. Still others say the name was that of a young black stable boy. The term Jim Crow is now used to describe laws and customs that restricted the rights of African-Americans, even after the Civil War, and following the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution.

These amendments were passed immediately following the Civil War. The 13th (1865) officially abolished slavery. The 14th amendment (1868) declared those people born in the United States were American citizens. The 15th amendment (1870) prohibited voting discrimination based on race, color, or previous slavery. (Interestingly, this did not stop discrimination against women voting. That would come with the 19th amendment.)

Rice, a struggling performer, very scarcely blessed with any talent, actually did little skits between the scenes at different theaters where he would wear burned cork blackface makeup, and sing with a silly and magnified accent.

This deplorable and highly exaggerated stereotype of a black individual was seen by large audiences throughout the United States, London and Dublin. By 1838, the term Jim Crow was being used pejoratively as a racial slur. But after the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation, the term was used to describe laws and customs which continued to segregate black people, such as the practice of sending the twins, Mark and Luke Roberts, to another county, just in order to prevent them from attending school with white youth.

Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896)

“Dad, how was your trip to Florida with the Gennetts?” I asked as Dad and Mom hugged and kissed in the kitchen upon his return.

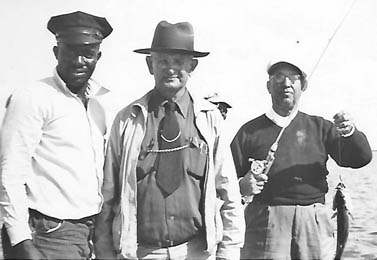

Photo courtesy Dr. Thomas Cloer III

Chauffeur Arnold, W.T. Cloer and Nat Gennett are pictured fishing in Florida in the 1950s.

The owner of Gennett Lumber Co. had asked my dad and my grandpa to go with him on a fishing trip to Florida as a reward for creating company wealth with Dad’s sawing skills using the shotgun steam-fed carriage, and for Grandpa W.T. serving as superintendent of the big band sawmill.

“You know Arnold, my good black friend who is Mr. Gennett’s chauffeur?” Dad asked.

“Sure, what about Arnold?” I answered.

“Well, we stopped down about the Georgia-Florida state line near Valdosta to spend the night, and the owner of the motel said Arnold couldn’t stay inside!” Dad said as he laid his suitcase on the bed.

“What happened then?” I asked in disbelief.

“That was going to be the case wherever we stayed,” Dad said. “I gave Arnold my pistol, and he took it, thanked me, and stayed all night in the car; that ain’t right,” Dad said before he started talking about the good fishing in Florida.

This was still another brush with Jim Crow laws as I was growing up in Southern Appalachia. I thought Arnold was really cool in his uniform and special cap. He always treated me nicely when he and I interacted. I could tell he had a wonderful personality, a good sense of humor and he was always shaking hands. He was especially fond of Dad and Grandpa.

I remember the time Mr. Gennett was visiting his sawmill and, as always, wanted some of Grandma’s good home cooking. Mr. Gennett told Grandpa W.T. that Arnold could eat outside. Grandpa forever ingratiated himself with Arnold when Grandpa told the president of the company that there would be none of that in his home. Arnold was a very special guest and was to be treated exactly in that manner.

Grandpa W.T. always amazed me with his skill in managing men at the mills. When he spoke, it was with authority. There was no misunderstanding by anyone that day concerning who was in charge regarding Arnold’s status at the lunch table in the home of W.T. and Pearl Cloer.

During the 1870s, in the aftermath of the Civil War, different states passed Jim Crow laws to undermine those new amendments to the United States Constitution. The United States Supreme Court had to determine if such Jim Crow laws as segregation of public schools, hotels, motels, restaurants, beaches, restrooms, drinking fountains and restrictions on interracial marriage were constitutional.

Plessy vs. Ferguson in 1896 was a landmark Supreme Court case that set the tone in America concerning race relations until I became an adult. The United States Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of “separate but equal.” The justices ruled that if facilities such as schools were separate but equal, they were constitutional. That United States Supreme Court ruling would ultimately be the reason that the Roberts family and the chauffeur, Arnold, would live as they lived on a day-to-day basis for much of the 20th century.

The Family of Floyd and Elnora Roberts

Mark and Luke’s father, Floyd William Roberts, was the only child born to Lester and Alice Roberts in Ellijay, Ga., on May 20, 1908. Floyd’s grandfather, Fayette, and great grandfather, Granville, had been slaves. When they became free, they took the last name of their owner, who was a Roberts. Floyd married Elnora Harshaw in September 1923, just when the tulip poplar trees around our Northcutt Community were beginning to turn yellow. They were married at the same little Pleasant Grove Church that I would visit in the 1950s.

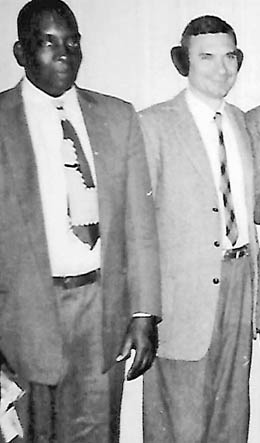

Photo courtesy Dr. Thomas Cloer III

Floyd Roberts, left, with Albert Harrison, president of Ellijay Telephone Co., at a Christmas social in the 1950s.

Their first three of nine children were girls. Ardella was born Feb. 6, 1926; Frances was born June 11, 1928; Frankie was born March 30, 1930. All three were born in Gilmer County in Ellijay, Ga. Frances and Frankie Roberts both graduated from Washington High School in Atlanta and continued in higher education to become nurses. Both became highly successful licensed nurses with careers devoted to helping others. Their father and mother instilled in all their children the need for education, and the religious zeal for helping others. Floyd had to be a very religious man; he lived with Mark, Luke and John. John Roberts was actually Floyd’s elderly uncle, who lived with Floyd and Elnora in their simple little home in our Northcutt Community.

The twins, Mark and Luke, were born April 26, 1939, in Ellijay. The children of Floyd Roberts rode in the car, furnished by Gilmer County, to the town of Tate, in Pickens County, Ga., to attend school with other black youth. Joe Charles and Horace were closer to my age, and would sneak looks at me when I would attend Pleasant Grove Church with my family. Horace was the same age as my brother, Nat, 3 years older than I, and Joe Charles was just one year older than me. Because of Jim Crow laws, it was unthinkable that reciprocity would occur, and Horace and Joe Charles attend our foot-washing white church, Northcutt Baptist Church, just up the road, almost in walking distance of Pleasant Grove. Thus was the madness when otherwise sensible people followed customs that were denigrating, deplorable and devastating to people who deserved much better.

Attending Pleasant Grove Church

“Tom, we’re going back to Floyd Roberts’ church Sunday, the black church,” Mom said.

“Your dad saw Floyd in town at the Ellijay Telephone Company where Floyd works as a janitor, and Floyd would not hear of anything but us attending their Homecoming. You and Nat liked it when you two went there last time,” she said as she dried the dishes and put them on the boards that served as shelves.

“Why can’t Floyd and his wife bring Horace and Joe Charles and come to our church? It would be neat to see someone from our church wash Joe Charles’ black feet, wouldn’t it, Mom?”

Mom paused and searched for something to say.

“Tom, that ain’t gonna happen.”

“Why ain’t it?”

“Please, son, black and white people like to go to their own churches, I reckon.”

“Then, why are we going to Joe Charles and Horace’s church, but they don’t come to ours?” I quarreled.

“Get out of here and burn off some of that arguing energy by picking beans; they’re turning yellow from being too mature,” Mom said in desperation.

Next week — Part 2: Jim Crow in Southern Appalachia in the 1950s.

About the author: Dr. Cloer is Professor Emeritus, Furman University. Dr. Cloer was honored as a recipient of the 2004 Maiden Invitational Award from Furman University’s Office of Multicultural Affairs. The honor is awarded to one faculty member annually at Furman for outstanding assistance to international and minority students.

[/cointent_lockedcontent]