Mournful and reflective Mother’s Day

Mom passed from this life at 5:48 p.m. on the eve of Mother’s Day 2016. The expressions of sympathy and care from far and near were phenomenal. Following is her eulogy that I gave at the funeral and have been asked to publish.

By Dr. Thomas Cloer, Jr.

Special to The Courier

Humble Beginnings

Grace Moody Cloer was the second child of Andrew Weaver Moody and Bonnie Woody Moody. Grace was born just below the Moody Bridge located across the Tuckaseegee River in the idyllic Tuckaseegee Gorge, just above Western Carolina University and Sylva, N.C., on scenic Highway 107.

Mom was born Nov. 11, 1924, in a little mountain cabin on the huge Moody farm in Jackson County, N.C. The small cabin was straight across the river from a cemetery on a high hill, where five previous generations of her ancestors lie. Those ancestors include Mom’s great-great-great-grandmother, who was born in 1749, approximately three decades prior to the Declaration of Independence. There’s a big fishing hole located there in the curve of the river named for her mother, called to this day the Bonnie Moody Hole. Bonnie was an extraordinary lady who loved to fish and hunt until contracting a dreaded virus in the mid 1940s that paralyzed her and nearly took her life. Bonnie then became crippled for life. Mom’s Dad, Weaver Moody, took a bad cold just before Christmas 1927, and died on Christmas Day when Grace was three years old.

decades prior to the Declaration of Independence. There’s a big fishing hole located there in the curve of the river named for her mother, called to this day the Bonnie Moody Hole. Bonnie was an extraordinary lady who loved to fish and hunt until contracting a dreaded virus in the mid 1940s that paralyzed her and nearly took her life. Bonnie then became crippled for life. Mom’s Dad, Weaver Moody, took a bad cold just before Christmas 1927, and died on Christmas Day when Grace was three years old.

Courtesy photo

Grace Moody, center, with sisters Maxine, left, and Lucy as caretakers of the Lupton Estate.

Bonnie Moody, needing work because of the Great Depression, moved her family to the Fred Lupton Estate at Sapphire, N.C. Bonnie became caretaker of the land and holdings. A beautiful mountain lake there provided Grace and her sisters, Lucy and Maxine Moody, and a brother, Fred Moody, with an excellent, luxurious swimming hole. Thus began Mom’s lifelong love of the water.

Love of Water

One of my first memories is of Mom in her bright red bathing suit hitting the water and swimming like a duck to my amazement after

Courtesy photo

Grace and Lucy Moody.

diving from the bed of a lumber truck backed deeply into the icy water of Holly Creek in the North Georgia mountains. Mom never missed an opportunity to swim, even in her 80s. She looked forward to rising before daylight, driving to Central, where my son, Carl Thomas Cloer lll (Tom-Tom), was director of recreation. Mom went swimming first thing early in the morning, even after her neuropathy and arthritis had limited her mobility.

Grace’s family outings almost always included large pools of mountain ice water that would exclude — even paralyze — flatlanders, but were simply delightful and rejuvenating to Grace, her husband, Carl, and her sons, with the exception of my youngest brother, Mike. He was afraid of the water until my older brother, Nat, and I healed him. We threw him in over his head and screamed, “Swim!” He swam.

Mom as Teenager and Young Adult

Just after Mom’s 16th birthday, she ran away to Walhalla and eloped with a carefree young mountain man, Carl T. Cloer, who was several years older than she — seven years, as a matter of fact. I always begin to squirm when people start talking loud, long and loathingly about young women marrying older men. They are talking, unknowingly of course, about my mother. Mom said people talked then and said it wouldn’t last. Mom and Dad “went steady” for 56 years.

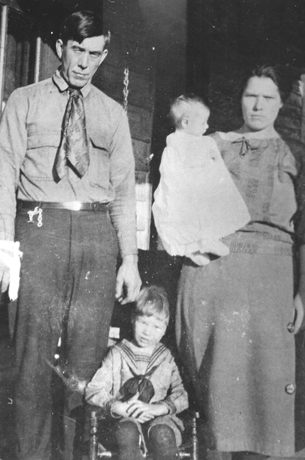

Courtesy photo

Baby Grace Moody, father, mother and brother, Fred, at birth place.

In 1941, Mom and Dad moved to Hayesville, N.C., where Carl T. Sr., and his brothers would operate a huge steam band saw mill for its superintendent, William Thad Cloer, my grandfather. Nat was born a year after Grace and Carl eloped. But I had the distinct honor of being the first to be born in a hospital, in nearby Murphy, N.C., in 1945.

The Cloers were sawmill nomads, and after my birth, the family moved to the North Georgia mountains to a little town called Ellijay. That’s where our family lived when Grace’s youngest son, Michael C., was born. Grace never missed a year being a grade mother in Nat’s and my school; she brought refreshments and fun to the children on all holidays. While other kids seemed embarrassed when their Moms came to school, I always loved for my Mom to come to the school, because all my classmates would say how pretty and funny she was, the latter being most important, of course. Mom would run, laugh and play with us as if she were an elementary pupil.

Mom always had a wonderfully earthy sense of humor. She has made her sons blush with that delightful, laid-back sense of humor, and whenever Dad felt himself getting too serious about life, he would always turn to Grace. When Mom could still walk around at the flea markets, I remember her embarrassing me one day by leaning over and saying, with only a slightly suppressed voice, “Tom, today must be Ugly Day at this crowded flea market.”

“Mom!”

Courtesy photo

Saw mill crew at Ellijay in the North Georgia mountains.

Move to the East Tennessee Mountains

Nat and I had attended the schools in Ellijay all our lives until 1959. I was entering the ninth grade, Nat was entering his senior year, and Mike his first year of school when the sawmill barons, who totally controlled our lives, moved the big band sawmill to Stinking Creek in the coal- and timber-rich high East Tennessee mountains. To say the least, Grace was not ecstatic about moving. But Mom made new friends quickly, and Nat and I never played a football game in the roughest mountains of East Tennessee that Mom missed. I can remember Mom laughing about us playing on an abandoned coal field in a coal mining town where the goalposts, for lack of space, were simply leaned up against a cliff of solid rock. One could literally mark the spot where the ball hit. It was their early version of instant replay.

Mom continued her role as being the finest chef ever when wild game and fish were the main dishes. Grace’s preparation of all species of fish, deer, turkey, wild boar, raccoon, woodchuck, squirrel, quail, doves and ducks was renowned. But Nat and I finally spoiled her with wild ducks. Because of snow and ice, we would be out of school for up to six weeks at a time in the Tennessee mountains. Nat and I had little to do but duck hunt. However, a family can only eat so many ducks, so Mom gave the ultimatum, “Not one more duck; I’m beginning to quack instead of talk!” she insisted.

But Mom had a totally different sentiment about squirrels, After we moved to South Carolina, every year in very early fall, about early September, Grace would say, “Tom, it’s time for a mess of squirrels, ain’it?”

And each year I would reply, “Mom, the squirrel season doesn’t open in South Carolina this early.”

And each year, Mom would reply, “Tom, you can open the season, get us five or six fat squirrels, and then close it right back.”

Grace Moody Cloer at cemetery across from her birth place.

Courtesy photo

Love of Nature

We have so many precious memories. There are the memories of camping, at times even without a tent — well, most of the time without a tent — and in state after state. Conditions that would scare most people into a state of panic were the very conditions in which the Cloers thrived. Deep forests and high mountains with few trails, rapid rivers and wild animals everywhere made the Cloers’ lives meaningful and exciting.

I remember one of the All-American athletes at Furman who got to know Tom-Tom well and hunted and camped with us when Dad was alive. He had absolutely never seen anyone like Dad. He thought Tom-Tom was a good shot until he took Dad bird hunting. The boy always hoped for a day bird hunting that might provide enough for table fare. Dad never missed a bird that day, and there was food for all. The athlete told his professors at Furman the following. He said, “If you took most people to the wilderness and set them out without preparation or shelter, they would perish. You take the Cloers and set them out in the same conditions with untamed wilderness, wild animals and roaring rivers, and then check on them in two or three weeks, and they will have gotten fat.”

Always Cheerful & Rarely Despondent

All of Mom’s family loved her. She was always so full of fun. With the exception of Dad’s passing, I can remember only two times when Mom was depressed to the point of weeping. One was when Mike, as a toddler, had contracted a dangerous lung disease, histoplasmosis, from his pet squirrel. I remember he had become scaringly emaciated, with dangerously high fevers, and was in rapid decline in the best hospital in Northern Georgia. I remember how Mom wept the evening the doctor told us he was afraid that Mike would not make it through another fever-stricken night. Mom frightened me when she genuinely wept in a manner I had never seen.

But Mike survived, and later in primary school, became manager of our football team in Tennessee. He then moved to Pickens, started playing football and became president of his senior class and starting center on a Pickens football team that never lost a game in the regular season — won them all.

Life-Changing Action

The other time that I saw Mom despondent involved me. It was the early 1960s. I was 16 and cocky. I had a heavy, dark beard at that age, played running back on the football team and was a member of the Beta Club Honor Society. Our little simple home was actually on the school property and was located adjacent to the Carpentry and Trades School Building. I regularly went home between classes. After counting the milk money one day, our inept principal, whom I will call Fretwell, called me to the office. Without making eye contact, he said tersely and choppily, “Cloer, the beard has to go.”

I replied, “Why are you so caught up with facial hair?”

He answered with 1960s certitude, “It’s a moral thing.” In the 1960s, this immediately set off a 16-year-old’s hypocrisy detector. I asked sarcastically, “What about your illicit and illegal affair with the new, married phys ed teacher that takes place almost daily after school hours in the Carpentry and Trades Building? Is that a ‘moral’ thing?”

He answered with 1960s certitude, “It’s a moral thing.” In the 1960s, this immediately set off a 16-year-old’s hypocrisy detector. I asked sarcastically, “What about your illicit and illegal affair with the new, married phys ed teacher that takes place almost daily after school hours in the Carpentry and Trades Building? Is that a ‘moral’ thing?”

Courtesy photo Author and wife, Elaine, at the grave of author’s great-great-great-great-grandmother.

To borrow a line from an old Kenny Rogers song, “For a minute I thought I was dead.” I have never seen such pent–up anger in a man as I saw that day. His answer was pathetic and woefully inappropriate. He simply wailed, “I despise you!”

Of course, this was exactly what a smart-aleck 16-year-old needed for a comeback. I answered probably in the most debate-winning and the most life-ruining way possible.

“Oh I know that! But you are evading the issue now, aren’t you?”

He then said the last words I believe he ever spoke to me. He said somewhat tiredly, “Go home! You are permanently expelled from this high school.”

I ran home, grabbed my fishing gear and sped off, thinking I was finally free. But Oh! Poor Mom! I will remember to my dying day how hurt she was! I wasn’t expecting that. She cried when she said, “Tom, you have to get along; you have to graduate from high school.”

I assured her I already was a fishing guide on Norris Lake and the Clinch River, and I was already making good money. Furthermore, I was a woodworker like my grandfather, and was already making really pretty furniture. Really! I would be just fine!

None of this placated Mom. I could see her growing more and more depressed each day I was out of school. I couldn’t stand to see her weep. What would you have done if you were in her shoes?

She was not dealing with just one jerk in this situation; I was involved, too. She had Dumb and Dumber who had to, someway, somehow, come to the only satisfactory solution for Mom — full readmission and graduation. I am amazed to this day the insight and political acumen my Mom showed in that situation. Mom knew the moral turpitude clause in the principal’s contract, with his hyper-testosterone levels, had numbered the days left in his professional life. She was so on target!

So she went above him. Mom persuaded the superintendent of Campbell County Schools to invite Tom Cloer back to school if Dumber would shave his beard. The superintendent called me, and, in the manner of Barney Fife, said he once had a mustache and understood my motivation. He also said he had watched me run the ball for the Jacksboro Golden Eagles football team, and would I consider shaving and finishing high school. I saw what a decent guy he was and said “Yes! Sure! I thank you for the invitation!” I was readmitted, graduated with honors and went to college.

This is the first time I have ever spoken publicly of Mom’s intercession. No one knew except Mom and me. I had never spoken of this to my brothers until very recently. My wife, Elaine, and I have been Mom’s primary caregiver since 2006, when Mom lost her ability to walk. Listen, I have simply been paying what I could along on a gargantuan bill, just trying to keep the interest paid, on an enormous debt I owed Mom.

*******************************

We will all miss Mamaw, but the precious memories will sustain us until we also travel to the other eternity at the end of our lives. For as a profound cowboy once said, “We’re all travelers in this world, from the sweet grass to the packing house, birth to death. We live and travel here between two eternities.” I look forward to the next.

“God bless you, Mom.”

About the author: Dr. Thomas Cloer Jr. received his bachelor’s degree from Cumberland College, his master’s degree from Clemson University and his Ph.D. from the University of South Carolina. He was the first Governor’s Professor of the Year for South Carolina.