Simplicity in Southern Appalachian life and speech

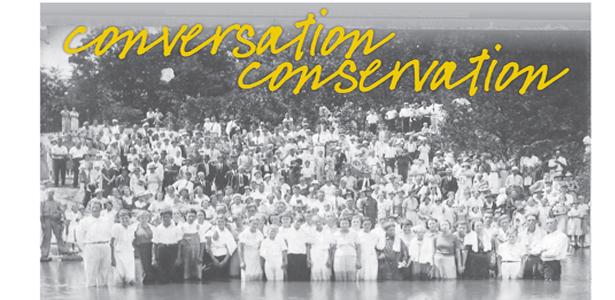

Above: Several of the author’s ancestors are pictured during a rural Appalachian baptizing ceremony unchanged in 2,000 years.

If there is one thing that my Southern Appalachian ancestors had to do when they settled here in the old Pickens District, it was to do things simply and to save.

My great-great-great-great grandfather Daniel Moody and his son, Martin Moody, were clear examples of this. Daniel was born in 1779 and came to upstate South Carolina in the 1790s. Daniel’s name appears in the 1800 Pendleton District census, and every census thereafter until his death in 1854. He is buried in the old Wolfpit Cemetery at Cheohee Community Center at Tamassee near his beloved granddaughters, Louisa and Martha Moody, who both died within a month of each other as teenagers.

Two of Daniel’s sons, Martin and Bennett Moody, were ministers to Cheohee Baptist Church in Tamassee at several different times during the early years of the church. Kay Alexander, author of “History of Cheohee Baptist Church,” gives us insight as to the simplicity of those times. She describes the church when Bennett Moody was pastor as “a one-room (to conserve heat) frame building with beaded ceiling and walls. It contained plank benches, kerosene wall lamps with a piece of tin behind each for reflection, and a large stove.”

To simplify things and conserve space in the little church, and because there was no water in the church, baptisms were held in nearby Cheohee Creek, just above the Cheohee Creek Bridge that still exists. In 1886, almost 50 years after my great-great-great grandfather Martin Moody was pastor there in 1838, the associational minutes listed the pastor’s salary at $8 a year.

It is no wonder to me why Martin stated in his will that the Confederate soldier, my great-great grandfather Daniel Van Buren Moody, and another son, John R., were to be left out of Martin’s will, for taking “a likely mare ” without consent. A horse was a big deal to the conserving pioneers, especially “a likely mare,” a young female that could give birth to colts. Whether for transportation, skidding with a sled, or plowing the fields, a horse was to be conserved.

Another example of the conservation of all things by Southern Appalachian mountaineers is one I will give of my paternal great-great grandfather, William Marcus Cloer (Mark), who also fought for the Confederacy and the 62nd North Carolina Regiment led by William Thomas, who later became chief of the Eastern Nation of Cherokees. I have letters that Mark wrote back home to Macon County, N.C. I also have letters that Mark’s father wrote to him. John B. Cloer was my great-great-great grandfather born in the late 1700s. It amazed me that there was mention, of all things, in several letters between the two, of a misplaced bell belonging to a cousin, Humphry Posey Cloer (Ump). The lost bell seemed to be a matter of grave concern. Ump was also in Company D of Thomas’ 62nd North Carolina Regiment. With more Americans killed in the Civil War than in all other American wars put together, why did a simple little bell hold significance to my paternal ancestors during this unimaginably horrific war? Just like the mare of my maternal ancestors, the bell held much significance because in the Nantahala Mountains of Macon County, N.C., it could help locate a lost ox, horse, ram, or sow if a bell was attached. One needed to save bells.

Conservation and Simplicity of my Youth

In the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, my life in sawmill villages of Southern Appalachia in North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and Pickens could be explained most by simplicity and saving. My family first had running water in the 1950s in the Turniptown section of Northern Georgia that President Jimmy Carter later bought. But that running water was simple. We stuck pipe back in a spring flowing out of a mountainside, wired a screen over the pipe’s end at the spring, and ran the pipe down the mountain into our simple and small mountain home. Although simple, there were drawbacks.

“Mom! What’s with the water? It tastes awful!”

“Tom, go up the mountain, look in the spring and see if you see something dead in the water.”

“I’ve already done that, Mom; they’s nothing there.”

The water got worse. The smell was overwhelming until one day a large dead salamander’s skinned head jutted out the spigot. It had pried under the screen! Drawbacks indeed! However, after Clorox liquid bleach had come on the market in 1913, it was a simple matter to pour it generously into our mountain spring. I last purified our shallow dug well here in Pickens in the same manner. We do things simply.

In the 1950s, our foot-washing Northcutt Baptist Church in the North Georgia mountains was not that different from my ancestors’ church here in the Pickens District in the 1800s. The major difference was a lightbulb that came to our North Georgia area in the 1930s. Our church was also a one-room frame building with plank benches and a wood stove for heat. Since there was no water, the deacons had to bring water for foot-washing. The Chastain ladies, living on Little Turniptown Creek, brought homemade wine for communion, and also brought white linen, because after washing feet, the preacher “began to wipe them with the towel wherewith he was girded” (John 13:5, KJV). Just like my early ancestors at Cheohee, my brother, Nat, and I were baptized outside in a deep hole in the Ellijay River at the mouth of Turniptown Creek. The church had not changed the activity since the Christ himself was baptized. We maintain our heritage in Southern Appalachia.

We had no indoor plumbing in our sawmill villages until the 1950s, but even with the gravity pipe coming down the mountain, we had no bathroom in our simple little mountain home. Dad decided we modernists should have a bathroom. Since there was no space for a bathroom, we decided to make a place on the porch. There were some drawbacks, the least of which was no heat. It gets cold in the mountains of Northern Georgia. I have written poetry about “Liking winter when the icicle splinters, and when cold mountain weather turns bathers into sprinters.” Some of the fastest sprints I ever made were across that porch and through to the wood heater and my clothes. Another more bothersome drawback was a kerosene heater that turned one black with soot.

We grew crops and raised everything we needed: chickens and eggs, hogs and pork, steers and beef, cows and milk. We were simple and we saved. Nothing was wasted that we grew. We canned beans, pickled corn, peaches, soup mixture, beets and many different vegetables. We cured hams and middling meat for bacon after slaughtering hogs around Thanksgiving. We were simple and we saved. Nat and I made our play things. We made sleds, soapbox cars, exercise bars, etc.

We conserved space and heat in our little mountain home at Turniptown by making the home smaller, and then installing and dismantling our heating system each year. We had a small wood heater that burned discarded slab and board ends, trimmed to raise the grade of the lumber at the sawmill. Of course, Mom also cooked on a wood cook stove that helped with the heating in winter.

In other ways, we were actually ahead of the times. For example, a common practice today is to enhance milk production by playing soothing musical sounds to dairy cows. During the summer months, Mom would have Nat and me pick a bushel of our half-runner beans, string them and then fill long lengths of threaded beans for hanging and drying on our front porch to produce “leather britches,” the best-tasting beans on earth when seasoned with a ham hock. I would turn on our first television as I threaded the beans with a needle, and Spurkey, our milk cow, would come, with no screens over windows, and thrust as much of her body as she could get in the window. She would stand for hours and enjoy our first TV. Her milk production was phenomenal, and she supplied us with sweet milk, buttermilk, cream and butter.

While it is true that anything but simplicity and conservation of all things drives most lives today, what I am hypothesizing is why so many of us from the Southern Appalachian Mountains conserve and simplify everything, including conversation and language in general. The past really does matter in explaining this.

Southern Appalachian Conservation and Simplicity With Language

“All right!” as they say. “Let’s start fishing and quit huntin’ bait!” I took about 100 of the most common verbs of English, and my finding regarding Southern Appalachian conservation with those action words was amazing!

Let’s look at sit, sat, sat. I sit down right now. I sat down yesterday. I have sat down every day this week. Now, let’s look at the transitive verb “set.” I will set the table. I set it yesterday. I have set it every day this week.

Along comes the Southern Appalachian mountain speaker. “Too many situations requiring too many verbs. Let’s save and simplify. We will use one verb, ‘set,’ for all six situations. I set down right now. I set down yesterday. I have set down every day this week. Furthermore, I set the table right now. I set it yesterday. I have set it every day this week. What’s your problem? Simplify and save; you only need one.”

The only variation I heard in my sawmill home-rooted language was with the old timers, some of whom used the word “sot” for past tense of sat. “He sot right down next to her.”

I can’t recall using the verb “sat” until I conjugated verbs for my teacher in “town school.”

Let us try another. Let’s look at lie, lay, lain. I lie down right now. I lay down yesterday. I have lain down every day this week. Now, let’s look at the transitive verb “lay.” I lay down the pencil right now. I laid it down yesterday. I have laid it down every day this week.

Along comes the Southern Appalachian Mountain speaker. “Too many situations requiring too many verbs. Let’s save and simplify. We can cover all six situations with lay and laid. I lay down right now. I laid down yesterday. I have laid down every day this week. I lay the pencil down right now. I laid it down yesterday. I have laid it down all week. What’s your problem? You only need lay and laid for all six situations. Simplify and save.”

I must admit. I never heard the word “lain” in the sawmill villages except when it meant not fatty — “This meat is really lain!”

You want more proof? When I looked at the irregular verbs blow, grow, know, and throw, I saw exactly the same phenomenon. In public English, I blow the candle now. I blew it yesterday. I have blown it every day. I grow onions today. I grew onions last year. I have grown onions for two years.

Along comes the Southern Appalachian Mountain speaker. “Too many verbs to remember. Do like you do with most words. Add ‘ed’, forget it, and go on about your business. I now blow out the candle. I blowed it out yesterday, I have blowed it out every day. What’s your problem? Simplify and save. Like saving 15 percent on your car insurance, that’s what we do. I know the answer now. I knowed it yesterday, I have knowed it every day. I throw the garbage in the can. I throwed it out yesterday. I have throwed it out every day.”

Still not convinced? There are reasons for actions. They come from somewhere. Let’s look at that verb “come.” Standard English: I come each day to the Pickens library. I came yesterday. I have come each day this week.

Along comes the Southern Appalachian Mountain speaker. “You don’t need ‘came’ in there. Just use ‘come’ each time like this: I come here to the flea market every Wednesday. I come here last Wednesday. I have come here to the flea market every Wednesday.”

My findings regarding what probably caused the conservation and simplifying of our language are most intriguing. I have only scratched the surface in this short exercise. Under space constraints I will give one more compelling example. Let’s take the common irregular verb “eat.” Standard English: I eat my lunch right now. I ate it yesterday. I have eaten it each day.

Along comes the Southern Appalachian Mountain speakers who have known nothing but simplifying and conserving all their lives. “We have three different verbs when one will do the job; let’s simplify. I eat my lunch right now. I eat it yesterday. I have eat it each day. You only need one. What’s your problem?”

Home-Rooted Versus Public Language

The fact that I am writing this article in Standard English is proof positive that a public language is necessary for public writing. I am only attempting to explain why a phenomenon occurs here in Pickens and elsewhere. The past is critical for understanding the present. There are many levels of language.

The first level is home-rooted language. It’s the first language one hears at the mother’s breast. It sounds right to our ears. It’s part of our inheritance. It’s native to our souls. It might be at variance with the next level, which is public language or Standard English. That’s no problem. All one has to do is add public language to one’s wardrobe. One does not need to be absolved of home-rooted language. Keep it and add as many other languages as you need. If one is to move upward in socio-economic sectors of America, it is simply necessary in most instances to add Standard English, (and maybe even learn the verb conjugations).

Public language is the language of the powerful, the elite, the ruling classes. If one chooses to become a member of those certain groups, one must be able to shift language patterns accordingly. What I want to assert here and now, however, is that it is immoral to suggest that we Southern Appalachian mountain people in Pickens and elsewhere, with our profoundly deep and meaningful heritage, must do away with our inherited home-rooted language. I keep mine in a special wardrobe and wear it whenever the occasion arises. I have multiple wardrobes of language. Once in a heated debate I asked a poor, confused member of the language police what right he had to tell 15 million self-reliant, rugged individualists, and very independent people of Southern Appalachia, how to speak. His response was so pathetically and woefully inadequate — “I have a Ph.D.,” he snapped back.

My response was even more inappropriate than his, and came totally from my home-rooted language. l euphemistically clean it up here.

“Horse manure!” I exclaimed.

About the Author: Dr. Thomas Cloer Jr. is Professor Emeritus, Furman University. His PhD. is from the University of South Carolina. He authored eight books for his language arts classes at Furman.