Analyzing the aftermath of Charles Silver’s killing

By Dr. Thomas Cloer, Jr.

Special to The Courier

Last week we introduced the killing of Charles Silver, on Dec. 22, 1831, by his petite teenage wife, Frankie Stewart Silver, in what was then Burke County, N.C.

Last week we introduced the killing of Charles Silver, on Dec. 22, 1831, by his petite teenage wife, Frankie Stewart Silver, in what was then Burke County, N.C.

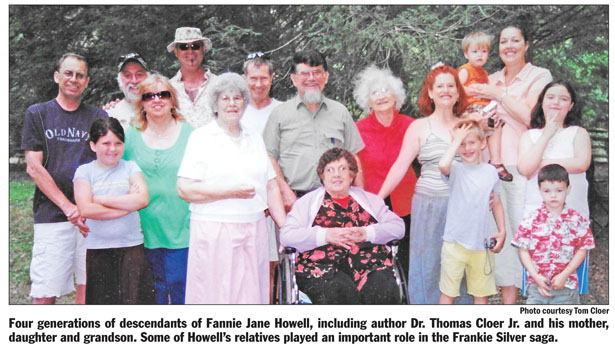

My Howell ancestors played a most significant role in this story. My great-grandmother was Fannie Jane Howell. Frankie’s mother was Barbara Howell, who married Isaiah Stewart.

My great-great-great-great-grandfather, James A Howell Sr., and his son, Thomas Howell, were key witnesses in the trial that sent Frankie to the gallows. So — what happened? I refer to Perry Deane Young’s 2012 book, “The Untold Story of Frankie Stewart: Was She Unjustly Hanged?” After the most thorough research in 187 years, I believe Young shows clearly that Frankie should not have been hanged.

Frankie panics

So, What happened? When her inebriated, abusive husband was loading his gun to kill Frankie and their 13-month-old baby, Frankie grabbed the closest thing — an ax — and struck at Charles’ head. The sharp ax — accidentally, I think — made a cut three inches long and one inch deep in the head of Charles Silver. Charles died instantly, according to the indictment.

Now, let’s get one thing straight: Frankie then messed up big time. Nobody disagrees with that. Remember, Frankie was a very young, illiterate, teenage mother who understood little about the world when she was at her best. When terrified with a dead and abusive husband at her feet, and a 13-month-old baby wailing, I conclude Frankie made all the wrong decisions. If she made a right decision after the killing, or had good advice for making a decision, I haven’t yet found it.

Frankie didn’t go to the sheriff. Frankie went to her family, the Stewarts. What happened subsequently at the scene of the killing will probably never be known. Astonishingly, Frankie eventually went to her Silver in-laws, sometime later, and asked if they knew where Charles was! Of course, that was the action of a horrified, confused and probably poorly prepped youngster.

“Has he returned from hunting?” she asked. Frankie said Charles had not returned home, and she was worried! (“Oh what a tangled web we weave, when at first we practice to deceive.” Sir Walter Scott was right.)

The hunting friend of Charles Silver, George Young, ancestor of the referenced writer, Perry Deane Young, said he hadn’t been hunting with Charles in weeks. Charles never went hunting without his dog, Drum. (Never heard of such an appropriate, creative name for a hunting dog with a booming voice.) That dog was at the cabin. Frankie was staying with her family, the Stewarts. Charles’ father, Jacob, began to get suspicious and called in the sheriff.

The hunting friend of Charles Silver, George Young, ancestor of the referenced writer, Perry Deane Young, said he hadn’t been hunting with Charles in weeks. Charles never went hunting without his dog, Drum. (Never heard of such an appropriate, creative name for a hunting dog with a booming voice.) That dog was at the cabin. Frankie was staying with her family, the Stewarts. Charles’ father, Jacob, began to get suspicious and called in the sheriff.

The sheriff went to the little cabin where Charles and Frankie Silver had lived. He first found blood drops in the cabin. He took up some flooring and found charred body parts. The sheriff also found a fancy heel iron, ostensibly from the hunting footwear of Charles Silver that, allegedly, my ancestor Thomas Howell had made in his blacksmith shop. Remember, there was no DNA in 1831. But if someone could prove that very unique heel iron belonged to Charles Silver, the charred body parts might likely be his as well. While circumstantial, the sheriff ruled there was enough evidence to make arrests.

Frankie Silver was arrested in January 1832. Frankie was now approximately 17 years old. Her mother, Barbara Howell Stewart, and her brother, Blackstone Stewart, were also arrested. The mother and son were believed to have assisted in disposing and hiding evidence. I, too, believe Frankie did not act alone after Charles was dead. I personally doubt that Frankie even returned to her cabin after going to her parents. However, there was not enough evidence to hold Barbara and Blackstone in jail, and they were eventually released. But poor, frightened Frankie remained in jail in Morganton, N.C., the county seat.

Bad lawyering

The old English common law was still in effect in North Carolina in 1832. People who were arrested in 1832 for a serious crime could not even testify if they pleaded “not guilty!” That did not change until 1857. Astonishing as it may seem, Frankie’s lawyer, Thomas Worth Wilson, had Frankie plead “not guilty!” Sam Ervin, the brilliant and colorful senator from North Carolina during the Watergate hearings concerning President Richard Nixon, said that if Frankie could have taken the stand and testified that she killed in self-defense, she would have been acquitted. I conclude that bad lawyering was responsible for the hanging of Frankie Silver. If she had simply pleaded self-defense, she could have testified, told the truth and could have given her full side of the story.

Perry Deane Young is a modern writer who also had ancestors involved in the story of Frankie Silver. He, like Sen. Sam Ervin, concluded that Frankie was hanged unjustly. Young meticulously reviewed everything reviewable, interviewed, ran down every lead and studied anything remotely connected to this public hanging of this pretty, frightened Southern Appalachian teenager.

The #MeToo social media movement concerning sexual assault started me to thinking about Frankie. But unlike the 2018 movement, poor Frankie didn’t even get a chance in the two-day trial to give her version of what happened!

The trial lasted only two days, you say? That is amazingly true history. There is no written account of anything the lawyer for Frankie said in her defense. Frankie obviously never understood that killing is not necessarily a crime, or the state would be guilty of a crime each time the state killed someone for killing someone else.

Ancestor called again to testify

The jury, after the first day, March 29, 1832, retired for the evening. The next day they reported that they were deadlocked with ninr in favor of acquitting and only three maintaining that Frankie was guilty. The jury requested that they have further opportunity to ask questions of witnesses for the state. I noticed in Young’s book that Thomas Howell, my great-great-great-great uncle who allegedly made the shoe iron entered as evidence, was listed as the first of seven witnesses called by the state in Frankie’s trial. Then, Thomas Howell was listed again without a number. I assume that he was the one called back the next day to answer questions, and, therefore, was listed again without a number.

My ancestral uncle’s testimony must have had a tremendous impact on the deadlocked jury. I bet he identified the heel iron as his work, and testified that he had made it for the deceased, Charles Silver. The jury then returned a verdict. All 12 voted “guilty!” The judge ruled that Frankie be hanged in July 1832.

There had not been one peep from Frankie; she wasn’t allowed a word. Why didn’t the lawyer plead self-defense? There is no proof anywhere that he made a case for self-defense. While Frankie was not allowed to say anything, her lawyer certainly could. Frankie’s lawyer wasn’t even responsible for the appeals that followed. Appeal was automatic. Finally, only in the appeals, Frankie’s story was sadly told.

Sentiments change

When the word was first spread that Frankie Silver had killed her husband with an ax while he slept with their little girl, Nancy, people were enraged. When a truer tale was told about someone burning the body parts, people were horrified. When Thomas W. Wilson, Frankie’s lawyer, obviously failed to argue self-defense, many people probably thought that all the tales about killing Charles while he slept were true. The tragedy of apparent butchering and attempted burning of the body parts by someone added to the horror.

Frankie stayed 18 months in jail, a very long time, from Jan. 10, 1832, until her hanging on July 12, 1833. Except for the eight days when she escaped, she was housed in a dungeon-like setting where she suffered greatly. People began to speak and hear about Charles’ cruelty to Frankie. Spousal abuse had even been approved as a reason for granting a divorce in 1814. While not exactly as forceful as the #MeToo movement of 2018, recognizing in any manner the spousal abuse of this era was a very significant step forward for women. Keep in mind that women could not vote, nor hold public office. It was stated in the appeal to Gov. Montfort Stokes that the cruelty of Charles to his wife was well known.

Attempts to save a frightened girl

Perry Deane Young’s book reviewed all the writing on Frankie’s behalf to try to save her life. It was mentioned that the evidence, the shoe iron my ancestor Uncle Thomas Howell had allegedly made and testified about at least three times, was totally circumstantial. Frankie’s very young age, her humble upbringing and her being sick in a dungeon for so long were all used to ask for a pardon. The word “brutal” was used to describe Charles’ behavior toward his young wife. Two petitions for a pardon were signed by 153 men! The second petition was also signed by members of families who were neighbors of the Silvers and Stewarts. Those four families included my Howell ancestors. The documents asking for a pardon were also signed by my Howell ancestors who had been called as witnesses by the state. A lawyer in Morganton, David Newland, wrote Gov. Stokes that he had discovered that seven of the 12 jurors of Frankie’s trial had even signed the petition for a pardon.

There is a record showing Frankie’s lawyer wrote a letter asking Gov. Stokes to grant a pardon just prior to the governor leaving office to become an Indian commissioner in Oklahoma. Stokes readily punted to the next governor, David L. Swain. Swain was the last chance that Frankie had. He never punted! To continue the football metaphor, he just went to the locker room and bolted the door.

Again, Perry Deane Young offers insight. Gov. Swain only served one term and was ousted as governor. He moved to Chapel Hill in 1936 and served as president of the University of North Carolina from 1836 to 1868. Now hear this! He was responsible for the founding of the North Carolina Historical Society. Young says Swain collected all printed and even handwritten items concerning the history of North Carolina. I’ll tell you what Young found in Swain’s papers about poor Frankie’s case. I’ll tell you in the Elizabethan manner my Yancey County ancestors would have said it — “They ain’t nary word ‘bout Frankie’s case; not nary word!”

I believe Swain might have been like Scarlett in Margaret Mitchell’s “Gone With the Wind,” when she said, “I can’t think about that right now. If I do, I’d go crazy. I’ll think about that tomorrow.” Or, was it because Gov. Swain had been labeled as one who was always giving pardons? Regardless, he must have seen himself as losing, however he ruled. Therefore, it might be best not to collect, save or say anything. He was the only one left to legally save Frankie. We know that Gov. Swain knew that a frightened young girl was soon going to die because Swain wrote a letter to her! He said for Frankie to prepare for her death in two weeks.

Attempt to live another summer

Frankie had now exhausted all means of appeal, so she did the only thing possible to live another summer — escape. What is amazing to me is the fact that she could escape from that dungeon, make it to another county and be free for eight days. She cut her hair short and dressed in men’s clothing. She played her part perfectly well, but her uncle “messed up.” Young’s book claimed her father and uncle were involved with another unknown person.

Danny McBee’s 1997 genealogical book, “Descendants of William Howell,” said that Jackson Stewart, the brother of Frankie, married Elizabeth Betty Howell. She was my great-great-great-great aunt, was sister to Thomas Howell the blacksmith, and to my great-great-great grandfather William A. (Billy) Howell. The book also says that Jackson helped his father and uncle with the escape.

The escape was working, and the escapee had made it to Rutherford County when the sheriff came upon a wagon of hay with someone walking beside it. Frankie had allegedly been hiding under the hay, but was now walking. The sheriff rode up and said, “Frankie?”

The reply in a deep boy’s voice was “My name’s Tommy.” The uncle responded, “Yeah! Her name is Tommy.”

The sheriff was no dummy. He immediately arrested the group and took them to jail. Young’s book mentions the father, an uncle and another unnamed person. I believe Jackson, the husband of Elizabeth Betty Howell, was the one who helped from the inside. I think he was probably the one who made the false keys used to open all the doors and leave nothing broken. Why do I think that? Jackson was bright and, interestingly, became the high sheriff of Mitchell County, N.C. Jackson was later murdered by a group of Union sympathizers in November 1864. This added more to the tales about “the curse on the Stewart family.”

The hanging

The hanging took place in Morganton, N.C., on July 12, 1833. There is much speculation about how it occurred. There is one thing that happened that should make it clear how Frankie was killed by the state. The wealthy women of Morganton were very vociferous about not wanting the hanging to occur. By the time she was to be hanged, most people had heard that she was abused and that she had fought back in self-defense of herself and the baby. The women of Morganton thus saw to it that impoverished, abused and condemned Frankie had at least one beautiful white dress in her lifetime — the one she wore to her execution.

The dress should also immediately give one insight about the manner of hanging. It would have to occur so that no one saw below Frankie’s waist. After all, there were ideals of decorum and propriety, warped as they were, that could not and would not be abridged. Frankie probably was hanged by use of a scaffold where those allowed to view it could see her from the waist up, once she had hanged and her spinal column had been severed.

It was written in newspapers that a confession was made before the hanging. Frankie “confessed” to killing her husband in self-defense. When asked if she had any last words on the gallows, Frankie’s father, Isaiah, allegedly called out, “Take it to the grave with you, Frankie.” I think I know what he meant. I have never found a word proving that any other Stewart family member was ever punished for hiding and disposing of evidence, or aiding with the escape. I believe Isaiah Stewart called out because he did not want to see any more family members punished.

The burial

I can just visualize that old wagon of the Stewart family with the rough, planked coffin in the back heading up toward the distant mountains for burial. It was July and very hot. There is doubt as to how far the Stewart family went outside of Morganton before the family started worrying about Frankie’s body decomposing. There is no information as to how long the body was in custody before being released. Regardless, the Stewarts obviously believed they could not make it to their home in Kona. It is believed they didn’t make it far before deciding something had to be done.

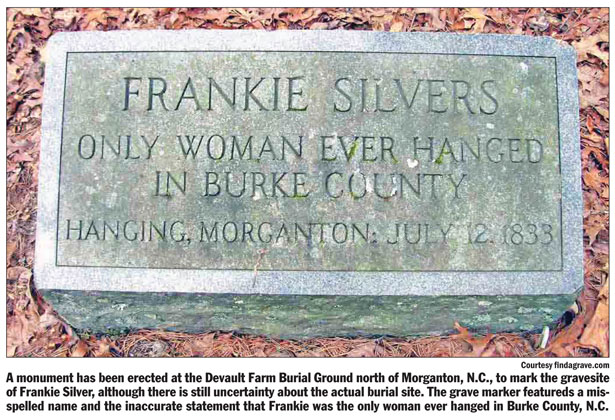

There is to this day uncertainty about the actual burial site. However, as with all stories of history, indeterminacies will be satisfied, one way or the other. In that vein, Beatrice Cobb, owner and publisher of the Morganton News-Herald Newspaper in 1952, placed a monument to Frankie at the Devault Farm Burial Ground. The Devault Farm is about nine miles north of Morganton on Highway 126. Legend has it that a child reported a wagon stopping and people hurriedly burying a wooden box near the Devault Farm.

The monument erected had two errors. The name of Frankie Silver was misspelled. The tombstone read also that she was the only woman ever hanged in Burke County, which is false.

Conclusion

Whenever I tell this story, people always ask me, “What happened to Nancy, the baby?” Not only was Frankie a teenage wife, she was a teenage mother. Records state that Nancy was raised by “a grandmother,” not “grandparents.” The grandmother would have to be Barbara Howell Stewart. Barbara’s husband, Isaiah, was killed by a falling tree in 1836, not long after Frankie was hanged in 1833. The Rev. Jacob Silver lived to be 97 years old. Furthermore, although the Silver family still claims their family raised Nancy, the records state otherwise. Nancy was “bound unto Barbara Stewart until she is 18 years of age.”

Nancy married David Parker, who fought for the Confederacy. Theirs was a great marriage, producing six children. The Civil War ruined their happiness. David Parker was wounded several times and died in 1865, just days after Robert E. Lee’s surrender.

Nancy moved to Macon County, N.C., where my Cloer ancestors were living. On Jan. 10, 1872, Nancy married William C. Robinson, and the marriage was a disaster. Nancy said that her second husband raped one of her daughters from Nancy’s marriage to Parker. Nancy ran Robinson off and took back her first husband’s surname. Nancy died Sept. 30, 1901. Nancy Parker’s tombstone is in the Mount Grove Cemetery in Macon County, N.C. A stone honoring her first husband is also there.

“The curse” on the Stewart Family is supported by the later hanging of Blackstone Stewart for stealing a mule. Remember, Blackstone was arrested for disposing of evidence and released in Frankie’s case.

I’ve thought much about what verdict Frankie would have received if she had done the same thing in today’s world and had enough money to pay a good defense lawyer. Might it be “Guilty of not telling the truth about family members practicing cremation without the proper license?”

The author is a Furman University professor emeritus. He was the first professor at Furman to win both Meritorious Teaching and Meritorious Advising awards. He was the first South Carolina Governor’s Professor of the Year, being chosen by the Office of the Governor and the South Carolina Commission on Higher Education. He has written extensively about his Southern Appalachian sawmill ancestry.