Looking for the ‘Roots of Literacy’

An Appalachian historical perspective

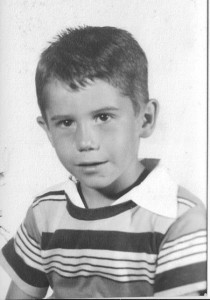

By Dr. Thomas Cloer Jr.

Editor’s Note: This is the first half of a two-part analysis of the roots of literacy by Courier contributor Dr. Thomas Cloer Jr.

You obviously are a reader. If you were not, you wouldn’t be reading this. Lately, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about what caused some to be voracious readers and others not to be interested. What makes a reader? What is it that propels some to read everything they can, and others to have an attention span with print just barely long enough to read a T-shirt?

I had the grand opportunity of working with some amazing professors from across America as we decided to examine our own literacy roots in an attempt to answer the questions raised in the first paragraph. What literacy roots do literate people have? In our gaggle of mossy-backed professors were people from such diverse places as Oregon, Wisconsin, Illinois, and good old Pickens, S.C. The professors were from very diverse cultural backgrounds, representing different ethnicities and varied perspectives. I was the only individual among the group, however, with a nomadic Appalachian sawmill village background. I came from “a road less gravelled.” There were about 30 participants in all who told some fascinating stories.

We were all getting long in the tooth and had been in academe long enough for us all to have somewhat similar brains. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) would reveal some brain features we all had in common. For example, the Committee Avoidance Lobe in each of our brains would show up huge and bright red. We were also at the stage in our lives where brain scans would reveal that we rarely heard, read, or saw anything educationally that had not simply been repackaged, rehashed or reheated with a new sign on it. Brain scans would fail to find the Genuinely New Educational Information Region in any of our brain hemispheres.

What happened on this search for literacy roots was most revealing. I genuinely thought that the mossy-backs would talk about great books that had interested them. All in the group had read various great works, and any of the individuals could have held forth ad nauseam; that didn’t happen. Instead, these professors and I talked about literacy events with people that had profound and memorable effects on our development as literate beings. We talked about our life-changing teachers and the pleasant and positive emotions that we remembered down through the ages because of these teachers’ inviting acts. These inviting, emotional episodes had made us feel valuable, capable, and responsible. As we are heading toward the end of the latest school year, many teachers in Pickens County are once again positively affecting the future by realizing that every student at every level is asking the ancient Biblical question, “Who do you say that I am?”

Many teachers will answer the Biblical question formally and informally, verbally and nonverbally, with inviting acts that say, “You are valuable, capable, and responsible; I respect you and trust you, and am glad you are part of my class.” These teachers prophesy that their pupils most definitely will be successful, and then fulfill those prophesies by choreographing positive, emotionally satisfying literacy events with their young readers. Teachers take on immortality this way.

My Home-Rooted Language

All my formative years were spent in Appalachian sawmill villages. I was part of a nomadic extended family of sawmillers living in sawmill villages on Turniptown Creek in the mountains of Northern Georgia, near Shooting Creek in Western North Carolina, and on Stinking Creek in the high East Tennessee mountains. My home-rooted language was unadulterated Appalachian. It was really much later that I learned public language almost as a second language.

President Jimmy Carter always thought Turniptown in the mountains of North Georgia was one of the finest places on earth. I guess after living in Plains, Ga., any hill looks beautiful. Turniptown Creek was a pristine and premier fly-fishing trout stream, and President Carter loved to fly fish. In the 1950s I regularly waded Turniptown Creek barefoot with my Dad, and we fly fished and furnished our table with trout for six months of the year, March through August. President Carter later bought most of it, and the Secret Service checkpoint was right above Turniptown Baptist Church. President Carter loved to woodwork with black walnut. He carved the collection plates for Turniptown Baptist Church from walnut and renamed most of the Turniptown area “Walnut Mountain.” I don’t know why he and Mrs. Carter didn’t name it Turniptown Heights or Turniptown Estates. Since he bought all the most pristine property at the highest altitudes where Dad, my brother, Nat, and I caught all three species of brook, rainbow, and brown trout, I always thought the president and first lady should have melodically named the property, “The Jeweled Crown of Turniptown.”

My paternal Grandpa and Grandma, whom I worshipped, were two of my language models that I revered and tried to emulate. Grandma’s folks had moved into Hanging Dog (my birthplace in Western North Carolina) and had intermarried with the Wolf Clan of the Cherokees. Grandma was uncanny when it came to catching native trout. As a constant companion, she taught me with explanations that might have been puzzling to anyone outside the sawmill villages.

Grandma’s pronoun for second-person plural was “you’uns,” and anything belonging to “you’uns” was “yorenses.” Example: “Hits up to you-uns to git the fish; hit’s yorenses job.” Grandma would interchange parts of speech very easily and change verbs and nouns: “You can git you one more gittin of fish now.” Or, “Fish gittin ain’t settin down work.” Of course the most easily recognized influence on our dialect was the Scotch/Irish influence on the “r” sound. Grandma had me get wood for the “far”. Grandma had to “arn” her clothes and hang them on the “clotheswarr” (clotheswire or clothesline). She couldn’t wear clothes “all gaumed up.”

“Meller” was one of Grandpa’s favorite words. It meant “beat till mellow” as in “I’ll meller his head if he messes with yorenses log trucks.” or “You want yore head mellered?” “Ary” was substituted for “any” and “nary” for “not any” as in: “Nary one of em wanted their heads mellered, and ary one of you’uns coulda done it.”

The Appalachian mountain culture was such that my ancestors lived largely to themselves. Their language was almost as different and individualistic as they were. However, there was a recognizable blending of old-world culture with an indigenous mountain culture. “Feisty” is from Middle English; “peart” and “atwixt,” from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. “Begun” was used for “began” as in “When he begun a little feisty, the other man started acting peart, right thar atwixt a heap o’folks.”

Appalachian speech repeated with vividness without being monotonous as in “You women folks might cook up some of that ham meat and biscuit bread for the preacher man.” Nouns and verbs were interchanged regularly, as in “Was thar a give-out at the meeting about churchin’ one of the Cloers for tale-bearin?”

Listening, Speaking,

Dramatization —

Nourishment for Roots

While isolation in the mountains affected our individualism, speech and independence, it did not stifle imagination so critical to literacy. My listening skills were well developed from the radio. My first viewing of a television came years after I had learned to read and had been in school several years. I can remember the anticipation of hearing such treats on the radio as: Lum and Abner, the Great Guildersleeve, the Lone Ranger, and the most suspenseful program ever, The Creaking Door. Listening has something to do with imagination and is a similar receptive language process to reading; its early development is highly related to later reading achievement. Listening to a story on radio is very different from listening to blather while viewing a television sitcom.

Other important factors in my literacy roots were dramatization and storytelling. I can remember the dramatization of revival meetings we had witnessed where evangelists conspired and perspired, sinners jumped and ran forward, and feet were washed by the humble brethren. We “acted out” revivals, weddings, funerals, foot washings, vocations (teacher, preacher, sawmiller, etc.), and anything else we could imagine.

Storytelling was a regular evening pastime. Telling haint tales was my favorite; these would start about dark. I can remember running barefoot a half mile from one end of the sawmill village to the other in about 15 seconds after it had grown dark and the last scary haint tale was finished. I am convinced that listening to others tell stories in those sawmill villages, and my retelling of those stories, had a tremendous impact on my love of writing.

Another impact that I am sure was critical to my early literacy was the presence of verbose female cousins in the sawmill village that read to me, engaged in drama with me, told stories to me and wrote stories in my presence.

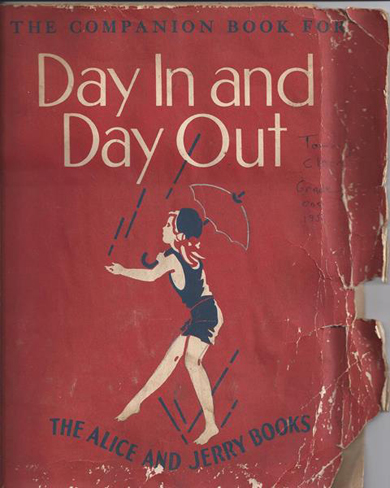

I am convinced, and can show the research evidence to support it, that personal writing is a key to literacy. There is a hole in the hedge between reading and writing. For example, I am convinced that hearing sounds in words and knowing the letters that represent sounds of our language are critical for literacy. This is why adults trying to assist a young reader will say, “Take that word apart.” The more I study language, however, the more I see reading as “putting together” as opposed to “taking apart.” Therefore, through personal writing, through the act of spelling while writing, we best learn the letter sounds for meaningful reading. Why? Through personal, meaningful writing, the words break apart naturally when spelling . In 1951, I labeled everything in the house where Mom was working. She would help me spell as I sounded out the words: c-u-p, pl-a-t-e, ch-air, ta-ble. The way to teach phonics is through spelling!

I was astonished at how glibly my female cousins did each of these things. They were “little teachers,” always eager to explain, demonstrate and model to me how to spell, how to compose and how to write. Talking leads naturally to writing; writing leads naturally to reading. They were little teachers who made their thinking public. My many math and English teachers could have changed the world if they had made their thinking public, that is, thought out loud about how to use a strategy before releasing responsibility and asking students to do so. I always thrived in school when my teachers would say, “Watch me; I’ll work through this, or, I’ll model this and talk about what I’m doing in an attempt to help you when you try.”

I venerated my cousins who were demonstrators and who made declarative statements to me about their thinking. I tried to emulate their ways. They have since become successful entrepreneurs and own their own companies. They were intelligent, creative and imaginative, and were good influences on a sawdust-doodler who needed help in realizing his potential.

Dr. Thomas Cloer Jr. is Professor Emeritus, Furman University. He was awarded the Outstanding Alumni Award from his alma mater, Cumberland College in Williamsburg, Ky. He has received The Medal of Honor and has been inducted into The Hall of Honor at Cumberland.