Looking for the ‘Roots of Literacy’

The Tap Root

Answering the Biblical question

Editor’s Note: This is the second half of a two-part analysis of the roots of literacy by Courier contributor Dr. Thomas Cloer Jr. Last week, Dr. Cloer discussed the influence of family and surroundings on literacy.

The quintessential influence for me, however, came from a goddess of affirmation and pedagogy called Miss Hipp, my first teacher in “town school.” I, as every student in Pickens County schools in 2014, was asking my first teacher the ancient Biblical question, “Who do you say that I am?”

I remember vividly my first day in this big town school. With fear and trepidation, I had boarded a bus and ridden many miles from Turniptown sawmill village to a huge brick school with more children than I thought existed on earth. These boys in town school all wore “real pants” or pants that came halfway up. I wore overalls and brogans from the sawmill commissary, a sort of Wal-Mart in a closet that the lumber company established to meet our every need. As my older brother took my sweaty hand and led me apprehensively to still another brick building, heaven opened its portals and Miss Hipp greeted me at the door. It was both the most frightening and the most influential moment of my life. It was to concretize forever my self-esteem, my zeal to learn, and even my later adolescent development.

Miss Hipp was the most beautiful, the best-dressed, and by far the sweetest-smelling female I had ever imagined. She hadn’t made her clothes; they looked like real clothes from a town store. Her eyes danced as if she had a thousand stories to tell me. Her smile would open prison cells, mend a thousand hearts and raise the academic dead; I wanted to marry her after that first day.

“I’ve been waiting to meet Tom,” she beamed. “I heard he was coming and I wanted him in my class. He’ll be fine here, Nat; I will put his seat up close to mine where the two of us can be close.”

Miss Hipp was the first woman I had ever heard speak standard, public English, and she did so eloquently. She was a lady of high culture with a head full of sense and a heart of pure gold. I count myself very lucky to have crossed paths with her.

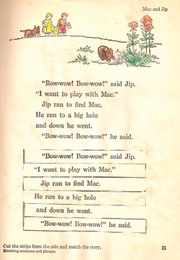

As I think back about those early literacy roots, I don’t believe methodology played much of a part. One can see that my Alice and Jerry books were not exemplary as to methodology. They were the source of the much maligned “Look and Say Method.” (Worked for me.) We were always cutting and pasting matched print after Miss Hipp modeled how to do so. Jerry in the innocuous stories was unlike any kid I had ever seen. He didn’t talk or act as I did. The dogs were upper-class canines. The one story that did resonate was the one shown here where the little dog went into a hole. Miss Hipp asked if anyone wanted to say what might be in the hole. She asked, “What was he after?”

My hand shot up! I said nervously. “It was probably a pole-cat (skunk), a groundhog (woodchuck) or a ground squirrel (chipmunk)!” Miss Hipp let me tell what I thought. Oh! Could I ever tell her what I thought! I told her what would happen if it was a pole-cat and how I knew those little short pants of Jerry’s would be squirted and smell awful! Miss Hipp would show that she respected my story by listening and having the other town children listen. The method didn’t matter as much as Miss Hipp. She knew the least little inviting act was like a feast for an emotionally starved sawmill boy asking the Biblical question.

What really accounted for the variance was Miss Hipp’s persona. When she was positively reinforcing me, the heavenly choirs would crescendo and reach their zenith as she exclaimed, “I’m proud you’re in my class!” She invited me formally and informally. She knew, for example, that greetings and good-byes were such important informal invitations. She respected me and showed that she trusted me to do what needed doing in her class. She acted like I had capabilities by inviting me to realize my human potential, join in the progress of civilization and join in the celebration of my existence. Everything she did was supernatural to me. She was patient, empathetic, always modeling how to do what she asked and always eager to help, even after releasing responsibility to me. She prophesied that I and the others would do well and then she forthrightly fulfilled her own carefully choreographed prophesies. She knew I needed invitations to develop my literacy roots the way the old Appalachian oaks need the rich mountain soil to develop theirs.

I am fully convinced that one of the most important school ingredients in the literacy development of most young males is an olfactory variable. I am in my seventh decade of life; I was only six when I first met Miss Hipp. Yet, I remember to this day, and will till I die, the ingratiating and pleasing smell of that woman. She had upon her neck and arms the sweetest nectar of the gods. Her breath was like one dozen fragrant yellow roses blooming, flowering and flourishing in my face. When she touched me tenderly, I had a hundred sweet passions surging through me.

I return regularly to the North Georgia mountains and visit with classmates. We invariably end up talking about Miss Hipp. Classmates have similar stories to mine. We refer to her as the Michelangelo of Ellijay. She, like the ancient sculptor who produced King David, would take an old rough piece of Appalachian granite, and would chip, chip away with informal and formal invitations, chip, chip, with nonverbal and verbal invitations until, in about nine months, she would rip away the canvas and reveal her work, “King Tom!”

The other teachers would ask, like the street urchins in Italy asked Michelangelo, “How did you know he was in there?” I can answer that. She, like all master teachers, and the Christ, saw potential in people that others overlooked. She was an incurable romantic, an eternal optimist, and had a vision of greatness for every person she taught.

Well, what about all the “disinviters,” the people in our lives who say formally or informally, verbally or nonverbally, that we are not very valuable, capable or responsible? What about those who store their toxic waste in others, the scud launchers, the psychological terrorists? Much of it is unintentional. Miss Hipp knew, though, as all master teachers do, that what is done with the spirit and emotions of a student is done forever. Miss Hipp also knew, however, that all the devils in hell couldn’t erase one single little dot over just one of the “i’s” in any invitation she had ever issued. What she had done was done forever.

Emotions are so critical to learning. Emotions and cognitive processes literally shape each other and can’t be separated. Emotions give meaning, color meaning, and warp and weave through everything we do in teaching and learning. Miss Hipp knew how to create community. Our brains are social brains. Part of who I was depended on finding a way to belong in Miss Hipp’s class. My learning was profoundly influenced by the nature of the social relationships within which I found myself in her classroom. She created true learning communities where we were valued as individuals. If we are really looking for genuine literacy roots in all the right places, we better surely look toward invitations that answer our Biblical question, and toward positive emotions as profound, immutable and unyielding effects on our early literary lives. I hope others were as lucky as I.

Epilogue

I

never asked Miss Hipp to marry me. It is impossible, still, for me to believe that she never married. After a long, truly remarkable and successful career, she retired from teaching, and moved to the West. She died there in the land of cowboys.

The Wolf Clan of the Cherokees shot many arrows at Hanging Dog. Miss Hipp died after shooting many living arrows into a time she didn’t get to see. I am honored and proud to be one of those living arrows with a message attached. She changed the world for the better; she shot forth positive messages and messengers. I never look at my picture on the horse without thinking of Miss Hipp. I wore that cowboy outfit to school after Christmas, 1951. Miss Hipp said I made a handsome cowboy. I wonder if I caused her to yearn for the West and the land of cowboys.

Dr. Thomas Cloer Jr. is Professor Emeritus, Furman University. He was awarded the Outstanding Alumni Award from his alma mater, Cumberland College in Williamsburg, Ky. He has received The Medal of Honor and has been inducted into The Hall of Honor at Cumberland.