A first-person perspective on Jim Crow in 1950s Southern Appalachia — part 2

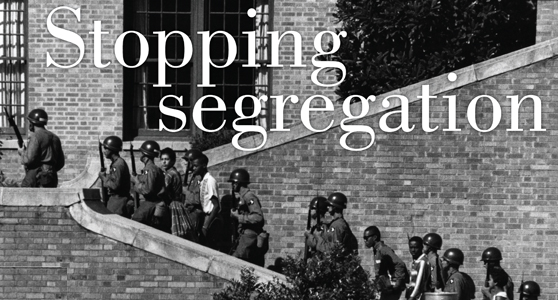

Federal troops escort “the Little Rock Nine” into Little Rock Central High School against the orders of Gov. Orval Faubus in 1957. Events such as the forced integration of LRCHS were characteristic of the struggle with integration around the South.

Courtesy photo

As we drove into the parking area at the black Pleasant Grove Church to attend Homecoming, I saw Mark and Luke, the African-American twins, walking into the church. They were talking and laughing with a very pretty black girl wearing a beautiful but simple white dress. The summer heat was stifling, and most of the girls wore similar cotton dresses.

When I entered the church building, it was obvious why they wore cotton dresses — it was hot! The windows were all opened wide, and every available handheld funeral home fan seemed to be taken. Some of the fans had a picture of a guardian angel helping two kids across a rickety bridge that was over a dangerous river, like the Conasauga River in the Cohutta Wilderness near where we were in the little mountain town of Ellijay, Ga. Dad, my brother, Nat, and I fished that dangerous river for rainbow and brown trout regularly. The other handheld fans had Leonardo da Vinci’s depiction of The Last Supper with Christ and his Disciples. Anyone not lucky enough to get one of the fans would use papers, hats, books or whatever was available to stir the air. Big black and red wasps would fly in and out the open windows. I was accustomed to that, because our old white, wooden, foot-washing Northcutt Church building was also blessed with summer heat and many, many wasps. However, in the aisle at Pleasant Grove, unlike our church, was an enormous metal wash tub like my mom used in washing our clothes. The wash tub was full of ice and very cold soft drinks, right in the aisle where the drinks were handy for Homecoming treats. I thought my church-going had already resulted in my going to Heaven. I most recently asked my brother, Nat, what he remembered most about Pleasant Grove Church, and it was the cold drinks in the big wash tub.

Mothers at our own foot-washing church would often bring cold drinks and cornbread or crackers and place them under the pews. I can vividly remember the quart and half-gallon jars of milk mothers would bring for the long revival services that would many times continue for hours with people lying in the altar.

As we walked into Pleasant Grove Church, Floyd Roberts met Dad and grabbed Dad’s hand with both of his. I heard him say, “Welcome, Mr. Cloer; thank you all for coming, and make yourselves at home.”

Nat and I looked at Joe Charles and Horace, Floyd Roberts’ boys who were close to our ages, and they looked back at us. We were caught in a time in history when nothing seemed that wrong to any of us; it just was as it was. I glanced at the twins, Mark and Luke, who had sat next to the pretty black girl in the white dress, and they looked confident, the way they did when we tried to play them in basketball — not like they did when walking in town. The pretty girl in the white dress was sitting next to the window, and could best turn around unnoticed. She stole a very brief glance at my older brother.

The preacher held his handkerchief in his hand and would thrust it upward toward Heaven as he exclaimed, “Jesus is our rock! You can depend on Jesus!” Immediately, the others in the church agreed and called, “Yes! Jesus is the rock!”

I looked at Mom and Dad to see how they were going to respond. I could tell they were interested and wanted to see what happened, too.

“Now, I want our Pleasant Grove Quartet to come up here and sing a special song for all our visitors today. We don’t want to embarrass no one, but if you are here as a visitor, please raise your hand!”

I was relieved to see several black people raise their hands.

I looked at Nat, Mom and Dad, and as they raised their hands, I timidly raised mine. Joe Charles, Horace and the twins looked at Nat and me as we both raised our hands. I didn’t quite understand then why the preacher had us raise our hands as visitors. There seemed to be something that immediately identified us. But, when I asked Dad later, he explained that was the way the black minister used to help make us feel special in their church. There were also black visitors he wanted to acknowledge.

“God bless you!” the preacher exclaimed when the visitors raised hands. “We want you to feel at home and worship our God in spirit and in truth,” the preacher exclaimed as he urged everyone to pray for the quartet as they sang.

Photo courtesy Dr. Thomas Cloer III

Floyd and Elnora Roberts are pictured during a social event in the 1950s.

When the singing began, it was very obvious that the singing came easily for them. The group was spiritual, talented, enthusiastic, and creative. Individuals in the quartet would improvise artistically. Songs were expanded; words and phrases were repeated. The singing was totally and beautifully authentic. I had never seen or heard anything quite like it. I thought they sang as naturally and skillfully as Mark and Luke excelled in basketball. I even managed to garner the nerve to clap my hands along with the members.

I felt terribly awkward when we dismissed and the twins walked by me.

“Hey, man!” Luke said as he glanced toward me.

“Hey, Luke! You still swishing that basketball net?” I said in an attempt to appear cool. Luke just grinned slightly.

I didn’t speak to Horace and Joe Charles. What would I say? Something like, “Now! It is your time. You must come to my church, Northcutt, next month, the third Sunday in August. We will have plenty of fresh fried okra, corn on the cob, and lots of coconut cake! Come and eat with us!” I didn’t run the show, nor did my fellow parishioners at our little humble Northcutt Church; Jim Crow laws did.

As we rode home in our bright red 1953 Dodge Ram, I asked, “Dad, if Floyd Roberts and his wife brought their family to our church, would our preacher say, ‘I don’t want to embarrass no one, but if you happen to be a visitor, would you help us by raising your hand?’”

Dad simply said, tiredly, “I doubt it.”

To use a line from Charles Dickens: “It was the best of times. It was the worst of times.”

Brown vs Board of Education (1954)

The death of Jim Crow laws was a very slow process. The beginning of the end was another landmark United States Supreme Court decision, a unanimous decision. The U.S. Supreme Court justices totally reversed the ruling of 58 years earlier that had declared “separate but equal” was constitutional. The court of 1954 ruled unanimously that even if school facilities were equal, and even if the faculty members were of equal quality, segregation itself was harmful and unconstitutional. The court held that “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The court further ruled that a significant psychological and social disadvantage was given to black students through segregation.

Alabama Gov. George Wallace stands defiant outside the doors of the University of Alabama to protest integration in the 1950s. Courtesy Photo

I think it is probably true when trying to change the status quo, change mostly comes about slowly around the edges, and not from the center. This 1954 court ruling came when I was still a youngster, and although a defining, pivotal point in history, things did not change suddenly. At the time of this court decision, 16 other states, not counting Georgia and Washington D.C., required segregation through Jim Crow laws. It really was not until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, under President Lyndon Johnson, that racial segregation, for the most part, finally ended.

I remember Gov. Lester Maddox of Georgia, and how he refused to serve African-Americans in his Pickrick Restaurant in Atlanta, even into the 1960s. I remember Gov. George Wallace of Alabama blocking the door so that a black student could not enter the University of Alabama in 1963. This was the year I finished high school, almost a decade after segregation was ruled unconstitutional in the United States. Do you remember Gov. Orval Faubus of Arkansas, who became governor after the 1954 court decision? In 1957, he ordered the Arkansas National Guard to block the integration of Little Rock Central High School, whereby President Dwight Eisenhower responded by federalizing the National Guard troops, and thereby putting the guard under federal jurisdiction.

Reflections and Conclusion

It has been many years since I knew the Roberts family in the Northcutt Community. I knew that Mark, Luke, Horace and Joe Charles had an older brother who had done extremely well, Jim Crow laws notwithstanding. A dear friend of mine still living in Gilmer County, Ga., sent me information on David W. Roberts, who was that older brother who also had gone to that black school in another county. He had subsequently received bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and had become a school administrator in Atlanta. He retired as an administrator after 30 years in Atlanta and returned to college to receive a degree in Biblical Studies. His years at Pleasant Grove Church had beckoned him back to his spiritual roots.

My dear friend in Gilmer County also has kept me informed about Mark, Luke, Horace and Joe Charles. All four married and had families. Mark held a position at Emory University for 30 years before retiring and moving, ironically, to Fayetteville, Ga. Fayette was the name of Mark’s great-grandfather, who had been a slave. Luke had died at age 50. Horace had attended Fort Valley University, married, and had three beautiful daughters. Joe Charles, the boy one year older than I, graduated from that black high school in Pickens County, Ga., and joined the Peace Corps. After his time in the Peace Corps, Joe Charles received his Bachelor of Science degree. He taught in the Atlanta schools, and subsequently worked for MARTA in Atlanta.

I was moved emotionally when I read the newspaper article from the local Ellijay Times-Courier newspaper that my old friend sent me. The heading read, “Only Black Man in Gilmer Is Dead.” The article had been written by Chet Fuller. I had known the Fuller family; Sandy Fuller was a former classmate and close friend of mine. The Fullers had also lived in my Northcutt Community, just down the road from the black Pleasant Grove Church. The writer also said, “He (Floyd Roberts) came from a long line of people born in this county,” but all the other people had either died or had moved. Even Floyd’s beloved Elnora had died two years earlier.

A second article written later about Floyd’s passing was titled, “Floyd Roberts Dies of Stroke.” The article had listed as honorary pallbearers some names of important and prominent people whom I recognized, such as Bandy Fuller, Glen Marshall and officers from various churches. Glen Marshall was president of The Bank of Ellijay, and was quoted in the article as having said, “His death will sadden the whole town. He was such a nice man and had so many friends here.”

Bandy Fuller was president of Hampton Mills, a rug manufacturing company in Ellijay.

“I wouldn’t doubt if the whole town turned out for his funeral,” the Hampton Mills president said. “He used to joke all the time about being the only black man left in all of Gilmer County, but would always end by saying how many friends he had. … Roberts was a religious man.”

The fact that all these important and well-positioned people felt a deep need to say positive things about Floyd Roberts and his family speaks volumes. The fact that my enduring friend would keep me informed about this particular family is telling. And as I am writing about this beloved family, even now, in a time Elnora, Floyd and Luke Roberts obviously didn’t ever get to see, is a testimony of their character, integrity, intelligence, diligence, resilience and value in my life. I, like so many other people of Gilmer County, Ga., will always remember the courageous and talented Roberts family of Northcutt Community in Ellijay, Ga., in the Southern Appalachian Mountains.

I also recommend metal tubs containing ice cold drinks in the aisles of our Pickens County churches during the unbearably hot dog days of summer.

About the author: Dr. Cloer is Professor Emeritus, Furman University. Dr. Cloer was honored as a recipient of the 2004 Maiden Invitational Award from Furman University’s Office of Multicultural Affairs. The honor is awarded to one faculty member annually at Furman for outstanding assistance to international and minority students.