A hero’s goodbye

I got some sad news from my best friend Allen Senn last week. Allen and I have been buddies ever since third grade, when we were the chief cut-ups in Mrs. Rauton’s class at Calhoun- Clemson Elementary School some 55 years ago.

Clemson Elementary School some 55 years ago.

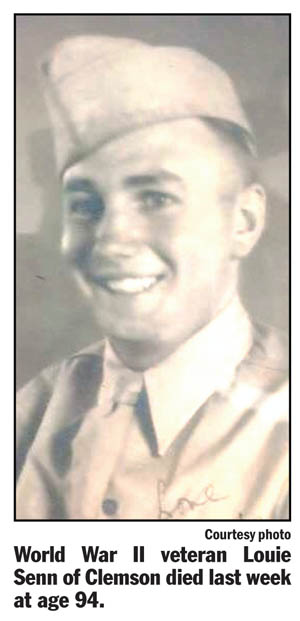

Allen texted me Monday to let me know that his dad, Louie Senn, had passed away at 3:41 p.m. Allen had told me just a few days earlier that his dad had been diagnosed with kidney failure and the doctor gave him just six months to live.

his dad had been diagnosed with kidney failure and the doctor gave him just six months to live.

“He is my hero,” Allen said.

Louie Senn was a World War II veteran who took part in the invasion of Normandy following D-Day. He grew up poor in rural Newberry County, came to Clemson to get an education and went on to have a distinguished career with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Clemson University.

Unfortunately, he didn’t live long enough after I got the word about his failing health for me to visit him again before he died.

But I got him to tell me his war stories a few years ago, and I’m going to relate some of that to you in a minute. First, though, I want to tell you about the adversity he overcame as a child.

Louie Senn, born Aug. 16, 1924, lived through some of the most difficult times imaginable as a boy.

When he was 9 years old, a hailstorm destroyed the family’s cotton crop, their only source of income. They had no money and couldn’t pay the taxes on their property, so they lost the farm.

Within a year, Louie’s father died, and he and his mother and older brother, Ed, moved from one relative to another without a home of their own for a while. Eventually, though, Louie’s mother inherited a bit of property and the family moved into a sharecropper’s shanty there, with no running water, and of course no electricity. This was in 1933, in the depths of the Great Depression.

Fortunately, they had good neighbors. The whole community of Pomaria came together and built them a small house — the type folks called a “shotgun shack.” But it was a big step up and cost the family nothing, other than what they paid a man to build a fireplace.

They were able to start farming again, growing cotton and a few crops and livestock for their own consumption.

So, by the time he was old enough, Louie headed off to Clemson College to study agricultural engineering. His college career was cut short, though, when he enlisted in the Army in 1943 at the age of 19.

He was in England when D-Day dawned. He was close enough to hear the bombardment from across the English Channel.

He arrived on the coast of France on June 10, 1944 — D-Day plus 4 — to a scene of unimaginable death and destruction.

“There were still bodies floating out there in the surf. There were still paratroopers hanging from the trees,” he told me, eyes closed, when I talked with him about it a few years ago.

His outfit was the 39th Infantry Regiment, which had an AAA insignia that stood for “Anything, Anytime, Anywhere.”

“That slogan was imprinted on our vehicles, on our helmets, and in our minds, I guess,” he told me.

They were assigned to clear a coastal village of German troops, which required making it down a road that was mined so thick that one of the tank commanders refused to lead the way.

“I remember very clearly my company commander holding up a pistol and telling him, ‘you’ll go, or you’re going to die right here,’” Louie said.

On June 21 — D-Day plus 15 — Louie’s unit was trying to take out a German pillbox — a machine gun enclosure — when he took a bullet in the leg.

He didn’t think he was hurt that badly, but the doctor at a field hospital told him he was lucky to be alive. The bullet struck right between his femur and an artery.

“A half-inch either way and you’d have been gone,” the doctor told him.

After winning two Battle Stars, he returned to Clemson on Dec. 30, 1945, finished his degree and joined the Army Reserve. He was recalled in the Korean War.

And now, I’m almost out of space and haven’t told you about how he went on to finish his bachelor’s degree and get a master’s and doctorate in entomology, and about all the interesting twists and turns of his career before he retired in 1986 as director of Regulatory and Public Service at Clemson.

You can’t boil down a 94-year-old man’s life story into a few inches of newsprint. But one thing he said when he told me that war story has stuck with me.

“It’s amazing how close you get to God when you’re about to die,” he had said.

I imagine he felt that way again in his final days.

May God bless you, Allen my friend, and all your family, as you face life without your dad. And may we all be reunited again someday on the other side.