A scary encounter with wild boars in the Pickens mountains

I am almost ashamed to recount this frightening encounter with wild hogs in this article. Some may wonder about my mental acumen. However, I will recount exactly how I planned to avoid disaster, and that might mitigate your thoughts of my possible mental deterioration — at least somewhat.

Unfortunately, wild hogs are everywhere in our state, including the Upstate. It is important to note that the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources encourages the harvesting of wild boars. They are destructive to habitat and voraciously eat all the food that falls to the forest floor. They root with their snouts, make destructive gullies and cause mountain erosion.

A Serene and Successful Hunt in the Pickens Mountains

I was hunting up U.S. Highway 178 in the Pickens mountains when I found unbelievable gullies made by wild hogs while rooting for acorns that were falling. I made myself a natural blind out of downed logs in mountain laurel. I sat for several evenings waiting for a boar to appear. I was situated so I could see all the gullies. After sitting for several trips, I decided to try and call a buck since the fall deer season was underway. I would call about every 20 minutes with grunts that, I thought, resembled a big buck wanting to mate and fight. The fighting instinct of mature bucks is at its peak in the fall.

I was hunting up U.S. Highway 178 in the Pickens mountains when I found unbelievable gullies made by wild hogs while rooting for acorns that were falling. I made myself a natural blind out of downed logs in mountain laurel. I sat for several evenings waiting for a boar to appear. I was situated so I could see all the gullies. After sitting for several trips, I decided to try and call a buck since the fall deer season was underway. I would call about every 20 minutes with grunts that, I thought, resembled a big buck wanting to mate and fight. The fighting instinct of mature bucks is at its peak in the fall.

Just before dusk, a huge reddish boar running full speed emerged from the thick mountain laurels. I normally make a sound to stop a running buck. However, I was afraid to try this on a boar. It was modern weapon season, and I had a rifle with a scope. I found the big boar in the scope, followed his running, saw the crosshairs on the hog’s heart and squeezed the trigger. The big boar fell dead in an old open logging road.

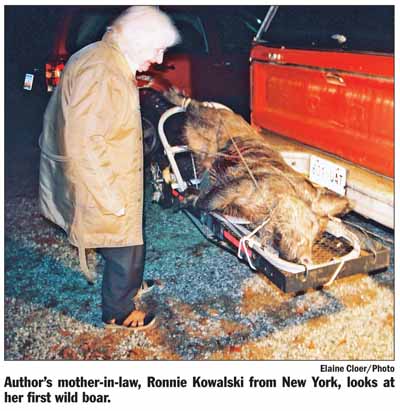

I returned to my truck via the old road up a very high ridge, and then realized I would have to bring the enormous beast uphill for an exhaustingly long pull. Our Pickens mountains can be really steep! Furthermore, it had started raining. I never go hunting without a pull cart with solid rubber wheels. I retrieved the cart and a raincoat from my locked truck, returned to the big hog and unfolded my cart. I tied him tightly to the cart, lifted the heavy load and started straining and pulling.

I was a running back in football for seven years. I would pull the beast uphill for a first-down distance, and then rest. If the old logging road was less of an incline, I would pull double the first down before resting. Suffice it to say, I was totally exhausted and very relieved to see the top of the high ridge where my truck was left.

From Serene and Peaceful to Frightening and Serious

For lands designated as Wildlife Management Areas (WMA), “Weapons used to hunt hogs are limited to the weapons that are allowed for the current open season.” In other words, if the season is primitive weapons on a WMA, one must use a primitive weapon, not a modern rifle. And one is not to wear a modern pistol in the primitive weapons season.

I have always enjoyed Daniel Booneing with a primitive weapon. My late dad and I had an Appalachian mountaineer friend who was an unbelievable gunsmith. We asked this man to make us two traditional homemade .50-caliber side-lock muzzle loaders with old iron sights and bird’s eye maple stocks. Side-lock muzzle loaders are traditional pioneer rifles with an ignition system exactly like many of the pioneer settlers used. First, black powder is placed into the barrel with the rifle butt down on the ground. Next, the projectile that serves as the bullet must be seated against the black powder. Dad and I used round balls (for more accuracy) with small patches that would hold the round ball in place. However, the round ball had to be tight, thus, hard to seat.

After one shot with black powder, the process is made more difficult because of the fouling that black powder causes inside the barrel. The spark that ignites the black powder comes from the side of the weapon (side-lock). There is a nipple on the side on which a percussion cap is placed to provide the spark that explodes through the side of the firearm to the powder in the barrel. Old Kentucky rifles, like the one I was using, have two triggers, one in front of the other. The back trigger sets the cock, but the front trigger actually drops the hammer on the cap and causes the explosion. Suffice it to say, this is all time-consuming at best, and downright dangerous at worst, if any steps are flawed.

Picking My Spot

The year of this encounter with wild hogs saw a record acorn crop. The most sought-after white oak acorns were plentiful in the very steep holler where I found so much hog sign. The ridges on either  side of the holler were high and covered with mature oaks that were all producing big, beautiful acorns. There were red oaks mixed in with the white oaks, and there were many huge oak branches overhanging the steep holler. Acorns were rolling into the hollow. Wild hogs were digging, rooting and destroying this picturesque site, one of the prettiest in the Upstate.

side of the holler were high and covered with mature oaks that were all producing big, beautiful acorns. There were red oaks mixed in with the white oaks, and there were many huge oak branches overhanging the steep holler. Acorns were rolling into the hollow. Wild hogs were digging, rooting and destroying this picturesque site, one of the prettiest in the Upstate.

It was September when I found all this, and muzzle loading season traditionally opens in October. I figured that I could take a wild hog with my old Kentucky homemade rifle. It shot straight, and as long as there was no moisture or specks of anything obstructive to the blasting cap, it was capable of doing the job, at least one time. I rigged two quick reloads by taking two small tubes with a capped end on each, and by putting a measured load of powder in each. I kept the round balls, patches and percussion caps where my hand immediately hit them in my jacket pocket.

I carefully selected the place I would hide. There were two very high banks in the steep holler. At the very top of one of the highest banks was a fallen chestnut oak. I made a place to sit down where I could rest my long muzzle loading barrel of 36 inches and shoot downward into the hollow. It would also make it very hard for a mad hog to get to me up the steep banks. I placed a barricade behind me in case the animal might come from that unfortunate direction. I wanted to eat the hog, and not the other way around.

The Morning of the Encounter

The first morning of muzzle loading season found me in that spot as daylight began to slowly brighten the dark hollow. A deer had bounded away as I arrived. I shined my light on the young deer as it made a quick exit. The squirrels were the first creatures I saw after daylight. Then, suddenly I heard grunting and strange guttural sounds. The hollow below me was soon full of movement as three huge wild hogs ran down into the acorns. I had already set the back trigger, so I cocked the Kentucky rifle and lifted it. I took careful aim on a wild boar’s heart and squeezed off the explosion. The gun blast was like a Roman candle at a New Year’s celebration. The smoke obscured the hollow, and I leaned down to see under the smoke.

The big hog that I had shot was down, but the other two were looking straight at me with demonic stares and acting really mad, making snorting and blowing sounds. I immediately grabbed one of my two quick loads and jerked free the lid on the powder. I loaded it while holding in my hand the round ball and patch. I quickly put the patch on the barrel opening and covered it with the ball. The ball sat in the very end of the barrel until I started it with a ball starter. By the time I had out my ramrod and was seating the ball, one big animal had decided to get me.

He made two or three attempts to clear the bank and reach the downed chestnut oak I was behind. I feverishly grabbed the tiny percussion cap, removed the spent one from the first shot, and replaced it with the other. By then, the big hog had managed to reach the chestnut oak log and was clamoring to get over it to get me! I shakily lifted the rifle, put the barrel right in front of the hog’s throat, and exploded the black powder. The boar kicked backward and rolled dead into the hollow. Guess what? Here came the third one.

I must admit, I figured the big creatures incorrectly. I thought when the first one fell, the other two would run away. I figured when two had fallen, the third one certainly would not continue the charge. I was almost “dead” wrong! The other one snorted and raked the dry leaves in a menacing fashion. I only had one more quick load. I repeated the process of getting the powder in as safely as I could. One cannot do it too quickly after firing, because the powder could explode. I wisely decided I did not have time for a patch. I also knew that after two shots, the inside of the barrel should be fouled enough for the ball to fit more tightly. I rammed my last ball in place. I nervously removed the spent percussion cap and applied a new one, because I had to fire. Just as I pulled off the explosion, the enormous boar jerked his big massive leg into the path of the bullet, but I missed his body. However, the big hog made his exit, limping. I had no more quick loads, but two huge loads of pork to get to my wife’s meat grinder.

Gaining Closure

I waited and went back to the holler when modern weapons were allowed. There were more hog tracks, rooting sign, and scraping after acorns, so I returned regularly for four weeks. The fourth week, I decided to stay and hunt until darkness stopped me. In the last five minutes that I could still see to shoot, the big hog appeared with a limp. I finished what I had started. I ended up eating them; they all three would have preferred the opposite.

I told my wife I had decided it was wiser to hunt dangerous wild boars with modern weapons. She suggested that when I first told her of my Daniel Boone intentions, she had thought my faulty plan had unlimited potential for improvement.

About the author: Dr. Cloer is professor emeritus, Furman University, and was the first South Carolina Governor’s Professor of the Year. His ancestors have lived in what is now Pickens County and have loved the mountains of Southern Appalachia since the 1700s.