Paying tribute to a friend for life

Most people have numerous friends over the course of their their lifetimes, and I’ve had quite a few.

They were co-workers, people I went to church with or played music with, mostly.

They were co-workers, people I went to church with or played music with, mostly.

But you can have only one best friend. He’s the one who’s always been there for you, for no reason other than because you like each other.

I’ve just lost mine.

If you’re a regular reader of this column, you’ve heard about him.

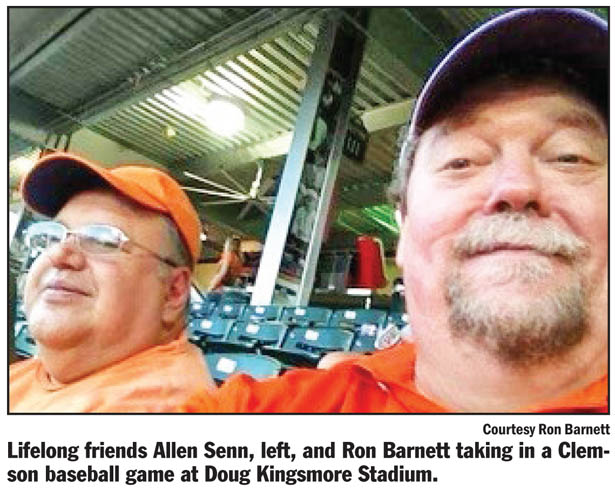

His name — and it’s very hard to use the past tense — was Allen Senn.

You knew him as co-founder and Senior Fellow, along with me, of the semi-fictitious two-man think tank, the Pickens County Institute for Advanced Theoretical Engineering, Economics and Barbecue Arts & Sciences.

I knew him as the best friend a guy could ever have.

We go way back, the two of us.

I met him in 1962, in the third grade, in Mrs. Rauton’s class at Calhoun-Clemson Elementary School.

Let me see if I can tell you something about why his friendship was so important to me.

You see, I was born with a fraternal twin brother, Paul Barnett. Sometime in our preschool years, I got the idea that nobody liked me. The kids I thought were my friends were really Paul’s friends.

When we got to first grade, they separated us. Suddenly, I was in a classroom with nobody I knew.

I guess I was pretty shy, because I didn’t really have any friends in the first and second grades.

I was kind of lost and lonely until I met Allen.

I’m not sure what it was about him that made me feel like I could be friends with him. Maybe it was that he had a unique way of walking that made him seem like maybe he felt as out of place as I did.

I never asked him until years later what caused his unusual gait. I assumed he’d had polio. Actually, it was something he was born with.

But it made it nearly impossible for him to make it to first base if he got a hit. And since I was the strikeout king, we were always the last two chosen when they picked sides at recess.

Since neither of us was athletically inclined, we found another activity in which we could excel: cutting up.

I don’t remember exactly what we did that had Mrs. Rauton pulling her hair out and sending us to the principal’s office with regularity.

But I remember the two of us spent many recesses sitting at our desks writing 100 times, “I will not throw paper airplanes in class,” and such things.

Of course such writing exercises did not reform us. We had a good old time cutting up in the empty classroom, which got us into even more trouble when the principal happened to listen in on the intercom.

Anyway, that was us, third through fifth grade.

I can’t go any further without acknowledging the passing of another old friend last week. I heard about it just a couple of days after Allen.

It was Lynn Rochester, the other guitar player in a rock band with me and my brother called Sashay — the band we were certain would take us to the big time.

Lynn was a short, crazy, very funny guy who played like Keith Richards. He was an electronics whiz and made his living fixing amplifiers after he left the band.

Lynn grew up in Clemson, but was living in Greenville during high school.

He had a heart attack.

So that added to the sadness in my heart that won’t be going away for a while.

I’m sorry this column is going to be too long.

But, back to Allen’s story…

The two of us went through Cub Scouts and Boy Scouts together.

Our dads both worked for the university, and we went to all the Clemson football games.

Allen and I watched the Project Mercury astronauts blast into orbit in third grade. It was Allen who, at recess in the fourth grade, gave me the news that President Kennedy had been shot.

In the fifth grade, our school burned down right before Christmas. Our class spent the rest of the year in a makeshift classroom in the basement of Central Elementary School.

My family moved across the lake into Oconee County the following year, and I had to switch to Seneca schools.

So Allen and I were separated until 11th grade, when we moved back to Clemson.

By then, a lot had changed. My brother and I had gotten into music and were more interested in playing in a band and doing things rock musicians do than anything else.

Allen, meanwhile, had become the equipment manager for the Daniel football team.

Since the “jocks” were sworn enemies of the “hippies,” we unfortunately never reconnected in high school. It was my fault, and I regret it.

He lived up to the Boy Scout Law. I didn’t.

After graduation, we parted ways again.

I saw him a few times over the years, but we didn’t reconnect until 2009, on Facebook.

Soon afterward, through his heart and with my journalistic assistance, we were able to get the governor — Nikki Haley — to tour and to see the value in a program in Greenville called Gateway House, which was in danger of shutting down because of budget cuts.

Allen didn’t have a degree in counseling, but he knew how to do it. I’m not a big talker with most people, but with him I found myself talking a lot, and him listening a lot.

But mostly over the years since then, we spent our time together sampling and critiquing all the regional hole-in-the-wall barbecue joints and home cooking restaurants.

And we developed Ron & Allen’s Old Clemson Barbecue Sauce, the best grilled chicken sauce on the planet.

We have ruminated at length over politics, history (he was an expert on the Civil War and World War II) and of course, Clemson sports.

In our think tank, we have solved — theoretically — most of the world’s problems, including how to harness and control hurricanes and how to eliminate the federal debt.

Unfortunately, my relationship with Allen the past three years has been mostly over the phone, because of the pandemic.

I had hoped to be able to get back to hanging out with him again soon.

The end of his time on earth came as a shock to everyone, after a traumatic fall.

He left us only three weeks before he would have turned 69.

I went to see him in the hospital that day, Feb. 11. He never regained consciousness while I was there.

But I talked to him and reminded him that he has always been and will always be my only best friend, and that I loved him like a brother.

I don’t know if he heard me, but he moved his mouth and made some sound.

I slipped a guitar pick into his hand so if he happened to wake up he would know I’d been there.

I was told that within an hour after I left, he was gone.

I had told him I hope to see him again “on the other side of the river.”

He wasn’t perfect and had his own troubles over the years, but if anybody ought to make it there, it would be him.

God bless you, buddy. I’m gonna miss you …

… Until we meet again, on that beautiful shore.