Run-ins with the dangerous creatures of the Jocassee Gorges

My children and grandchildren always loved the classic children’s book “Where the Wild Things Are,” by Maurice Sendak.

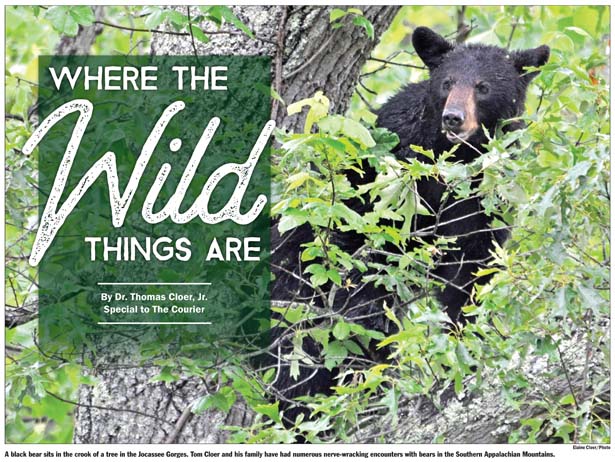

The Jocassee Gorges here in our county are full of wild things. While these wild animals may not be as bad as imagined by the main character, Max, in Sendak’s classic, there are still some dangers.

My ancestors and my immediate family have spent many wonderful hours collectively camping, picnicking, exploring, fishing, hunting and photographing in Jocassee and other wilderness areas in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. I will focus on incidents where I have felt genuinely threatened and in danger.

Nerve–wracking bear Encounters

Game Management Lands of the Jocassee Gorges are plentiful up U.S. Highway 178 that leads from Pickens to Rosman, N.C. Motorists only need to look for yellow and black signs that line Highway 178 to see that the lands available for public hunting are plentiful in our Jocassee Gorges and Franklin Gravely Game Management Area. It was up Highway 178 in the Jocassee Gorges that a scary incident occurred between a gigantic black bear and me.

I was deer hunting. I don’t bear hunt, because I don’t particularly care for bear meat, but I love venison. I had found a fresh buck scrape in a beautiful gap where white and red oak acorns where plentiful. Bucks scrape a clear place in rutting season and leave their scent. I had noticed bear scat,  but I did not particularly worry, because I figured the bear was just wandering through the area and was long gone. My natural blind was in the stump of a gigantic chestnut oak that had broken and left a hollow stump just the right height to get inside, see over and use for a gun rest. I constructed another natural blind just over the top of a dividing ridge that separated my gap from a totally different watershed.

but I did not particularly worry, because I figured the bear was just wandering through the area and was long gone. My natural blind was in the stump of a gigantic chestnut oak that had broken and left a hollow stump just the right height to get inside, see over and use for a gun rest. I constructed another natural blind just over the top of a dividing ridge that separated my gap from a totally different watershed.

I was sitting in that natural blind, looking over a different watershed, when I saw a huge black form emerge from the dense mountain laurels surrounding the blind in a grove of white oaks. I always fix my natural blinds with a dead sapling that I use to steady my gun to hit a target. When I peeped into my scope to view the black form, the crosshairs of my scope were between the eyes of the biggest black bear I had ever seen! I swallowed hard and enjoyed the fact that he was a good 50 yards away and never knew I was in the world.

Since I was eagerly anticipating the arrival of a nice buck, the next evening I decided to cross back over the high ridge and hunt out of the chestnut oak stump that had been so productive in the past. My next trip found me in my stump grunting and doe bleating to allure the scraping buck. The deer in rut had also horned and rubbed a good-sized sourwood sapling that I could see about 50 yards away. I sat and grunted like a buck and bleated like a doe about every 20 minutes. I could see for at least 100 yards down into the beautiful open gap surrounded by dense mountain laurel.

Just as it was approaching dusk, I was watching carefully down into the gap where I had taken several deer, a wild boar and an enormous coyote that came to my deer bleats. I heard a rustling in the leaves directly behind me where a split occurs in the stump. I swallowed my tongue when I eased my head around and the giant bruin — a black bear for the record books — was within 20 feet of me with my back to him! He had found some acorns, and he seemed more interested in devouring them than me. I pondered whether to call, wave, cough or die. Before I had to do either, he looked directly at my stump, raised his nose and sniffed. I started breathing again when the hair raised on his back, but he started taking steps meandering higher up the peak away from me.

I have encountered bears several times in the wild. I have photographed them numerous times, but was always careful not to violate their space. This incident genuinely frightened me. The bear was too close to a human, and neither he nor I knew it until we had violated the space rule. He was too big a bruin for that kind of mistake.

Unaware That He is There

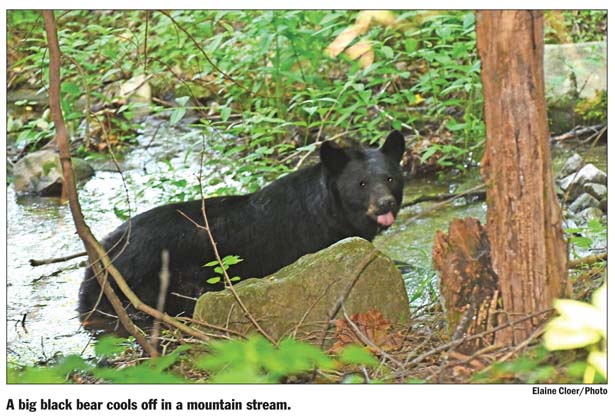

A similar violation of space involved my late Dad and me. He and I were high in the mountains at a great fly-fishing trout stream. We had hiked a good distance and wanted to examine our fly collection to see if we had something to match the natural hatch we had observed. We chose a mossy spot right where our feet rested against the edge of the clear, cold stream. The place had a high, overhanging bank that actually shaded where we sat. We couldn’t see above the bank because of the overhang.

As we sat there facing the stream, examining our collection, I thought I heard someone above us on the overhanging bank. I whispered to Dad, “I think we have competition.”

As I stood, an enormous male bear, unaware until then that we were under the bank, leaped off the bank, over our heads and into the stream, splashing water on us and everything else. Standing within a few feet of us in a huge pool in the mountain stream, the hair on his back stood straight, and he emitted a strange barking sound.

Dad and I started quickly downstream, as if stung by hornets, to create more space between us and the big boy with straight black hair. When he moved, he jumped to the opposite bank, gave another “Boof!” toward us, and then walked away indignantly.

Dad said, “What an experience! He was right above our heads and didn’t know we were under him.’’

I responded, “I’m glad he wasn’t any more PO’d than he was.”

Problem With Bear While Filming

My wife Elaine is a very fine photographer and filmmaker when it comes to wildlife. We often walk for miles while filming nature scenes with all their splendor. I will recount two different photo shoots that involved being scared by big bears.

for miles while filming nature scenes with all their splendor. I will recount two different photo shoots that involved being scared by big bears.

We were hiking when I caught glimpse of a big black bear digging away in the ground. As we approached and closed the distance between us, he only once stopped his digging, and that was to swat a swarm of yellow jackets on his nose. We then realized he was digging out a huge yellow jacket nest.

I warned Elaine not to get close, but she continued to slip up the slope toward the bear. She was busy filming when the bear suddenly detected her. He looked up with yellow jackets stinging his nose. His hair stood straight on his back. He gave a loud “Boof!” and leaped toward my wife. As she turned to run, she tripped over a root and fell hard to the ground. The big bear stopped and wondered what was happening. I quickly helped her to her feet, and we started down the slope. When we looked back, the big bear was walking back toward his hole with the swarming yellow jackets. I really think he was just protecting his find.

The next encounter was really comical. After finding a mother and her cubs, Elaine and I were filming from a safe distance. The cubs were playful and were running and jumping on small trees. They would occasionally wrestle with each other and investigate what their mother was eating.

Elaine and I were on a knoll looking down as the mother worked her way around the bottom of the knoll. She was lost from sight for a moment when I said, “Elaine, I don’t like being unable to see her. Let’s back away to that big fallen oak and make sure we don’t violate her space.”

We backed up to the big fallen oak. Just then, the big fallen oak with its dead boughs and dry leaves began to vibrate, then erupt with loud crashing as Elaine and I ran an Olympic sprint away from the noise. As I glanced back, there was an enormous eight-point buck standing tall watching two scared pilgrims. He had been in his bed when we backed up to him, too close for his comfort. Elaine and I thought the big mama bear was after us. We laugh often about our elderly reflexes and the record Olympic sprint.

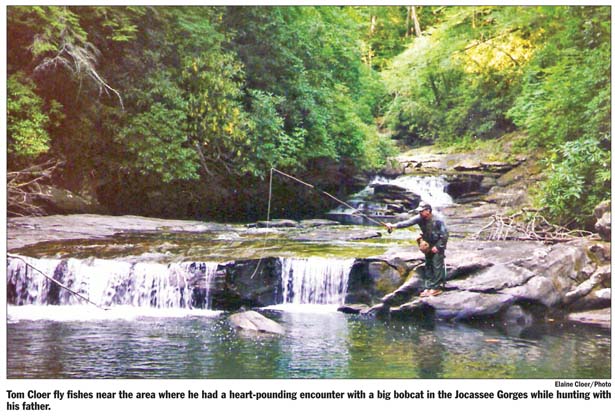

Unusual Encounter With a Bobcat

Another adventure involved a scary incident with an enormous bobcat who obviously thought I might be something that needed scratching. My late dad and I had found a big trophy buck pawing and rubbing his horns against trees on land open to hunting in the Jocassee Gorges. The open hunting land was near Howard Creek, south of Duke Energy’s Bad Creek project.

“You go with me up there and we’ll get that big buck,” Dad said as he took off his heavy coat.

“I can’t go until the week-end, but I’ll go then!’ I exclaimed as I patted Dad on the shoulder.

As was always the case, Dad was ready to go at least three hours before daylight the next Saturday.

“We’ll get set in our places and let our scent die before daylight,” Dad said, knowing that I’d rather wait a little closer toward daylight before starting.

“We’ll sit about a quarter of a mile apart on that old logging road in two different gaps where the buck scraped,” Dad said. “One of us will get a shot if we don’t mess it up.”

After a week at Furman teaching day and night classes, I felt the lost sleep when I reached my spot in a gap on the mountain. I had my homemade and comfortable camouflage cushion with large straps for tying around my waist. I sat at the base of a huge shagbark hickory tree, leaned back and very quickly dozed. The fresh night air in the Jocassee Gorges was cool and refreshing. I was dressed warmly, and my eyes closed as the sandman came. The next thing that happened was a small piece of the shagbark of that big tree hit me in the face. There was no wind, so I knew something was causing it when the second piece fell on me.

I leaned back, shined my flashlight and looked up the tree above me without standing. There within 12 feet of me with his head down staring straight at me was a big and most curious bobcat! I thought I would let him see that I was a person, and he would run away. I had covered my face with brown, green and black camouflage paint, and the big cat was obviously confused. When he started coming on down the tree, I quickly stood, waved my rifle and said “Go away now! Don’t be a pain!” However, the enormous and confused cat jumped down on the ground in front of me, and his bobtail started swaying as he started acting like he was going to pounce on me.

“Get away, you!” I said without raising my voice to a loud volume. I shined the bright light directly at the big cat and shook it. The big cat started inching toward me, his back hunched. He was just ready to pounce when I stuck out my rifle, waved it and put it to my shoulder. I said, much louder this time, “Get away! I mean it now! Leave me alone!” I again shook the light.

But, instead of spooking, he surprisingly became even more interested in me, and started easing directly toward me. I found him in my scope and tapped the trigger. The .30-06 blast scared me and everything else in the Jocassee Gorges. Furthermore, the big cat whirled and ran into the rhododendrons.

“Doggone it! Not only did I scare everything in the Jocassee Gorges by shooting at a dang bobcat, I don’t know if I even hit the cat!” It was still too dark to see. I thought that if I just sat still, Dad or I still might possibly get a shot at the buck after daybreak. It was late November, and while bobcat season was open, I never, ever, have wanted to shoot a bobcat.

The Plot Thickens

Daylight dawned as a bird began to tweet in the white oaks nearby. I arose in the noisy dry leaves and walked to where the huge cat had been standing when I fired. I immediately saw a small hickory sapling that I had not previously seen in the darkness. It was directly in front of where the big cat was standing when I shot. The small hickory sapling had a bullet hole squarely in the middle, and blasting out the back side.

On the other side of the sapling was cat fur everywhere. I found blood spots on leaves and started tracking. The tracks went to a spring head that seeped slowly from a cavernous hole under a huge rock. The blood trail went into that hole. I got down on all fours and shined a flashlight. Far back into the seep, I could see the big paws of the cat.

I immediately hooted to Dad as I imitated a barred owl. My family members for many generations have used this signal to communicate in wilderness when we want to reunite. Dad answered back with his distinct hoot.

When he reached me, I told him what had happened and that the big cat was there in the hole.

“Let’s find a big pole, and we’ll make a noose on it,” Dad said as he was already eyeing a particular small poplar sapling.

“You keep your rifle handy, and be ready to shoot, but be careful,” Dad said. “I saw a big briar that we can wrap around the sapling to help snag him. If he don’t make a sound, he’s dead.”

Dad carefully slid the poplar sapling back toward the big paws and made a snag the first trial.

“Get ready!” Dad said. He tugged, and there was no reaction. The big cat slid slowly toward us as Dad pulled with force. I was amazed at how long the big male animal was. He was a beautiful animal; I really felt bad about having to make a decision in a hurry while protecting myself. I was, after all, encroaching on his space.

When we examined the placement of the bullet hole, there was a slot the size of a dime directly behind his foreleg, in the vicinity of the cat’s heart. This happens when a high-powered bullet goes through something like hard hickory wood. Instead of expanding as usual, it flattens dramatically. When I held his back paws and reached the big cat as high in the air as I could, his front paws were still on the leaves.

I did exactly what I did not want to do — I messed up our hunt. Our excursion that day spooked the big buck, and Dad and I, despite our repeated efforts, never saw hide nor hair of the big buck doing all the rubbing and scraping.

Next week: Part 2 , Scary Encounter With Wild Boars