The wrongful hanging of a Southern Appalachian girl

By Dr. Thomas Cloer, Jr.

Special to The Courier

In the 1830s, my maternal Howell ancestors in Yancey County, N.C., were inextricably involved with  one of the most bizarre trials ever to occur in Southern Appalachia — and the subsequent hanging of a white teenage mother.

one of the most bizarre trials ever to occur in Southern Appalachia — and the subsequent hanging of a white teenage mother.

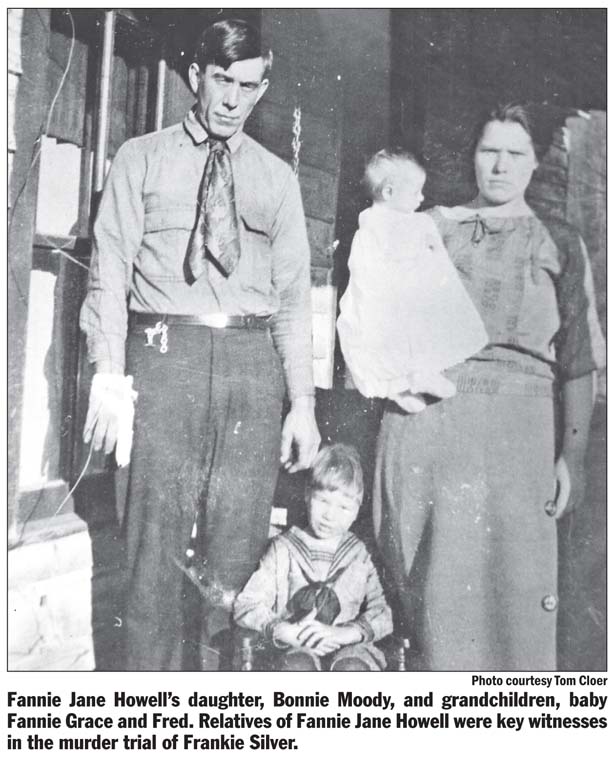

My mother’s name was Fannie Grace Cloer. She was a namesake of her maternal grandmother, Fannie Jane Howell, of Yancey County. My grandmother, Bonnie Missouri Woody, daughter of Fannie Jane Howell, lived in the remote mountains of Yancey County with Fannie Jane and Bonnie’s father, George Woody.

Introduction

The bizarre killing of Charles Silver in 1831 involved his pretty wife, Frances “Frankie” Stewart Silver. This took place in Kona, N.C., in what was then Burke County, near the North Carolina and Tennessee border. It is also close to where my great-great aunt Sarah Cloer West is buried just over on the Tennessee side of the rugged mountain. She lived to be an amazing 103 years old.

Legend holds that the “Toe” River Valley, the setting for this story, is said by many to be an abbreviation of our own Pickens County “Eastatoe.” The first white settlers in the Southern Appalachians called one tribe of Native Americans the Eastatoe Indians, although they were really Cherokee. Our Eastatoe Indians lived right here in what would one day be called Pickens County. Our huge, sprawling Eastatoe Valley was referred to as “The valley of the green birds.” This was apparently a reference to the native and now extinct Carolina parakeets.

The Toe River Valley of North Carolina is more than 300 square miles of sprawling valley, another place where the natives and Carolina parakeets once thrived. Others claim the river should have been spelled the “Tow River” for its swift current. I have actually seen that particular spelling on an old document. Next to where this bizarre killing occurred, the river probably had a powerful tow because of the rugged mountainous terrain.

Frankie Stewart Silver was a pretty teenager, weighing a petite 90 pounds, who was hanged in Burke County, N.C., at age 18 in 1833. This was the year Yancey County, where my Howell ancestors lived, was created from parts of Burke and Buncombe counties. Frankie’s mother was Barbara Howell Stewart (1778-1855).

I can think of no single killing in Southern Appalachia that has created more folklore, museums, ballads, books, magazine and newspaper articles, plays, etc., than this occurrence in which my Howell ancestors were so critically involved. I attended the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. “The Ballad of Frankie Silver” was a ballet about this story, written and performed by the Tanze Ensemble of Basel, Switzerland, as part of the cultural happenings surrounding the 1996 Olympics.

Background

My Howell ancestors came from Wales. They settled first in Virginia, and then moved to what would become Yancey County, N.C.. After their daughter was hanged July 12, 1833, in Morganton, N.C., county seat for then-Burke County, Frankie’s mother and father, Barbara Howell Stewart and Isaiah Stewart, lived in Yancey County. Isaiah (Ice) Stewart, died there first in 1836 when a limb from a chestnut tree he was cutting killed him. Barbara was bitten by an enormous rattlesnake and died there — suffering terribly — in 1855. This was only a part of the so-called “curse on the Stewart family.”

No Southern Appalachian story triggers more emotions for me than does the hanging of young Frankie. My great-great-great-great grandfather James Howell is listed on official documents of the trial as a witness called by the state. He, James A. Howell Sr., is also listed as head of household in the Burke County census from 1810 through 1830. The testimony of his son, Thomas Howell, a talented blacksmith and the brother of my great-great-great grandfather, William A. (Billy) Howell, was the most critical testimony to both the grand jury, and in the murder trial, that sent Frankie to the gallows. The 1997 genealogical book “Descendants of William Howell” by Danny McBee states that Thomas Howell made the shoe buckles or heel irons that someone allegedly tried to burn with the remains of Frankie’s husband, Charles Silver.

trial as a witness called by the state. He, James A. Howell Sr., is also listed as head of household in the Burke County census from 1810 through 1830. The testimony of his son, Thomas Howell, a talented blacksmith and the brother of my great-great-great grandfather, William A. (Billy) Howell, was the most critical testimony to both the grand jury, and in the murder trial, that sent Frankie to the gallows. The 1997 genealogical book “Descendants of William Howell” by Danny McBee states that Thomas Howell made the shoe buckles or heel irons that someone allegedly tried to burn with the remains of Frankie’s husband, Charles Silver.

I have not yet connected all the dots from Frankie’s mother, Barbara Howell Stewart, and my other Howell ancestors of Yancey County. My working hypothesis is that Barbara Howell Stewart is a distant cousin of my other Howell ancestors.

Furthermore, Elizabeth Betty Howell (1809-1888) was the sister of my great-great-great grandfather William A. (Billy) Howell. Elizabeth Betty Howell married a brother (Jackson) of Frankie Silver. Jackson Stewart was present at the hanging of his sister, and allegedly was one of the Stewart family members who helped Frankie escape before she was recaptured and executed.

A troubled marriage

Frankie Stewart came from a very poor home in Southern Appalachia. Poor homes in Southern Appalachia in the 1830s were woefully poor. When Frankie was 14 years old, she met a young teenager named Charles Silver, a neighbor of the Stewarts and the Howells, and Charles and Frankie soon were sparking. Charles was 17 and Frankie was 14 when they married.

The marriage was troubled from the beginning. Frankie and Charles had a baby, Nancy, one year after marrying. Charles loved strong drink. There is much information to suggest he was an abuser of alcohol and of a young wife. When he began to abuse strong alcohol, Charles wanted to beat up on Frankie. He became a terribly abusive husband, according to a large number of people who knew them.

Tragedy in a little one-room log cabin, located near my Howell ancestors, occurred just before Christmas on Dec. 22, 1831. On this night, while in a drunken rage, Frankie said Charles retrieved his gun and was loading it to kill Frankie and the 13-month-old baby. Frankie grabbed the only thing nearby, an ax, and struck Charles, killing him. The indictment said that the ax wound was three inches long and one inch deep. You can read these documents in a 2012 book. The book is by Perry Deane Young, and is titled “The Untold Story of Frankie Silver: Was She Unjustly Hanged?”

The Silver family’s view: Jealousy

Charles Silver’s father was Jacob Silver. He was a well-known mountain preacher. He was illiterate, but well respected in the Toe River Valley where he preached. Apparently, someone must have read the scriptures to him and he memorized sermons.

In one of the sawmill villages where I was raised, there was a well-known and respected preacher who could not read or write. It did not seem to matter with his parishioners whenever he spoke of ultimate truths. Many, if not most, of the listeners simply believed that the sermons “come from God.”

Many of the Silver family to this day believe and contend that Frankie murdered Charles out of jealousy and revenge. Charles was known to have a wandering eye and a thirst for mountain dew, and he liked sowing wild oats.

The following is the Silver family’s version of the killing: Charles Silver was going off on a hunt near Christmas. Frankie wanted him to cut enough wood to heat the cabin while he was gone. It was bitterly cold, and everything was frozen. Charles chopped up a whole hickory tree and stacked the split wood so it would be handy for Frankie. Charles was “give out” after all the manual labor and lay down in front of the fire place fast asleep with his head outstretched, holding little baby Nancy in his arms.

According to the Silver family, Frankie then, with Charles sound asleep, gently and carefully removed the baby from her husband’s arms, retrieved the ax and gave a hardy whack to Charles’ outstretched head. According to the Silver version, the blow didn’t kill Charles immediately, because he stood and cried out, “God bless the child!” Charles then fell. So Frankie supposedly gave a second whack to assure the job was done.

How could any member of the Silver family know this? They certainly never claimed that one of their family was present, except the deceased.

The Silver family held to the view that Frankie’s family helped in the killing. The Silver family maintained that the Stewarts wanted to move west, and Charles was said to be strongly opposed. (None of the Stewarts ever moved west.) Frankie’s lawyer actually wrote the governor, which I guess the poor lawyer thought might help Frankie. Young’s book documents that Frankie’s lawyer said he very much doubted she acted alone. Frankie had allegedly told others she would kill Charles, ostensibly meaning if he didn’t stop the abuse.

The Silver family believed that if Frankie Stewart’s family didn’t help in the killing, some of them helped in disposing of the body. I, too, think that’s probably true.

If only

Now, if only Frankie had taken her baby, gone to the sheriff, and said, “Oh, my God! I’ve killed my husband in self-defense. He was loading his gun to kill my crying baby and me. I’ll never live another day in my life that I won’t regret killing someone I loved more than my own life. It was either stop him, or he was going to kill my baby and me. My life is now ruined forever!”

That didn’t happen.

It is important to remember that we are talking about a young, illiterate girl who was just a teenager. Frankie had lived in dire poverty. She was not wise in the ways of the world. She was not knowledgeable in any sense of the word regarding law and how it was administered in America. She was a panicked, frightened youngster.

Furthermore, the Silver family had a prosecutor representing them who would be highly competent regarding the law. History about this case should have been totally different. The killing of Charles Silver would not have led to the hanging of a terrified and pretty little 90-pound impoverished, abused Southern Appalachian girl if two or three predictable, logical things would have happened.

If only Frankie’s lawyer had been competent, she would not have hanged. My wife’s dimmest, slowest cat (she now has 12), would have known to have Frankie plead self-defense. It is a universally understood fact that one threatened by a horrific situation that could cause one great bodily harm or death makes lawful the use of force, even with an ax. Killing someone with an ax would otherwise be ruled a crime, but not if it were to save the lives of these two people facing death by gunshot.

If only Frankie’s immediate family had done anything other than what I think they actually did, history would be so different. None of her family ever testified that I have discovered. Young’s book documents that only three witnesses were even called for the defendant. Furthermore, the trial lasted only two days!

Next week: The conclusion to “The wrongful hanging of a Southern Appalachian girl.”

The author is a Furman University professor emeritus. He was the first professor at Furman to win both Meritorious Teaching and Meritorious Advising awards. He was the first South Carolina Governor’s Professor of the Year, being chosen by the Office of the Governor and the South Carolina Commission on Higher Education. He has written extensively about his Southern Appalachian sawmill ancestry.