Why relive the racial problems of America’s past? Part 2

The study of history is paramount to advancing democracy

By Dr. Thomas Cloer Jr.

Special to The Courier

There is agreement among America’s higher institutions of learning that knowledge about the past is critical in a democracy. The study of history is paramount as we develop into a better democracy that recognizes the teaching in holy writ that says “Love thy neighbor as thyself.”

This is necessary for an advancing democracy. We in the USA have advanced from killing or running off the indigenous people, as was the case right here where we live. We have advanced from enslaving people brought to America and being sold as property. We have advanced from a Civil War that took more than 620,000 American lives. We must continue to advance.

Both GREAT-Great-Grandfathers Fought for the Confederacy

I know about heritage; I get it. My maternal great-great-grandfather, Dan V. Moody, from the Old Pickens District, was a casualty at Fredericksburg, Va. He was part of the Confederate Ransom’s Brigade led by Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom Jr. Dan V. Moody became a casualty on Dec. 13, 1862, in the most one-sided battle of the Civil War. Union casualties under Gen. Ambrose Burnside were more than twice those of the Confederates led by Robert E. Lee. The frontal attacks on Marye’s Heights, by the Union Gens. Edwin Sumner and Joseph Hooker, were totally futile. Dan V. Moody’s Confederate infantry used a huge stone wall as a barricade in the historic Sunken Road at the base of Marye’s Heights. The Confederate artillery on the high ground, facing in the same direction as the Confederate infantry behind the stone wall, fired safely over the heads of Dan Moody and his comrades at the base of Marye’s Heights.

I know about heritage; I get it. My maternal great-great-grandfather, Dan V. Moody, from the Old Pickens District, was a casualty at Fredericksburg, Va. He was part of the Confederate Ransom’s Brigade led by Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom Jr. Dan V. Moody became a casualty on Dec. 13, 1862, in the most one-sided battle of the Civil War. Union casualties under Gen. Ambrose Burnside were more than twice those of the Confederates led by Robert E. Lee. The frontal attacks on Marye’s Heights, by the Union Gens. Edwin Sumner and Joseph Hooker, were totally futile. Dan V. Moody’s Confederate infantry used a huge stone wall as a barricade in the historic Sunken Road at the base of Marye’s Heights. The Confederate artillery on the high ground, facing in the same direction as the Confederate infantry behind the stone wall, fired safely over the heads of Dan Moody and his comrades at the base of Marye’s Heights.

Gen. James Longstreet’s position on Marye’s Heights was devastating to the Union troops. If the advancing Union troops survived the artillery blasts and pushed forward, they encountered the impenetrable Confederate infantry behind the stone wall. Here was the opposite situation of that which occurred later at Gettysburg. At Gettysburg, the Union Army held the high ground at Big Round Top and at Little Round Top. There, the Confederates were out in the open, exposed and on the losing end. Fredericksburg, where my great-great-grandfather was a casualty, was one of the largest and deadliest battles of the Civil War. The Union Army had 12,600 casualties; the Confederates suffered 5,377 casualties.

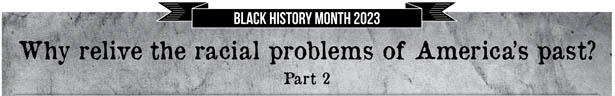

My paternal great-great-grandfather, William Marcus Cloer, was also a member of the Confederacy. I know about heritage. He was part of William Thomas’ 62nd Legion from North Carolina. William Thomas later became chief of the Eastern Cherokee Nation. Marcus Cloer became disenchanted with the Civil War. He went AWOL, came home to see his wife, and later went back to his company, wherein he was immediately incarcerated in a dismal Confederate prison. He stayed there for a month. I have his letters to my great-great-grandmother, Susan Cloer. These letters are gut-wrenching when Marcus talks about wanting to die, rather than stay alive. After release from the Confederate prison, his Confederate company went straight to the Cumberland Gap, where he was captured and sent to the horrific Union prison, Camp Douglas, in Chicago. This prison was constructed to house 4,000. By the end of the war, there were more than 12,000 Confederates there. At Camp Douglas, 6,000 Confederates were entombed in the largest Confederate cemetery outside of the South. Marcus Cloer stayed at Camp Douglas until the end of the Civil War. When he came home, he was unrecognizable and had to be disinfected before entering his mountain home in Macon County, N.C.

Why mention this? I want my readers to know I understand “heritage.” I also know that we have advanced greatly as a democracy since the Civil War. There are simply not that many people left who would argue for enslavement of a race of Americans. It is also chilling to think how hard it has been to get to where we are now. I can sit and eat with my black friends. They can stay at fine hotels when we speak at conferences. They can use public transit. But getting to this point in our democracy has involved much bloodshed. My ancestors, including those who were Confederates, were living in an infant democracy that was barely underway. We had to find our way to a different time, a time when women would vote, would work outside the home, and could own property. We had to advance. People with disabilities had to make it the best way they could. People who became elderly had to make it until death the best way they could. There was no Social Security or Medicare. We had to make advances as a democracy. Thank God, we are still advancing.

That is why I write today. I am in my twilight years. Most of the sand is in the bottom of my hourglass. I want to leave this world a better place than what it was when I was born. I was alive when Adolf Hitler was alive. I lived under Jim Crow segregation. I went through the civil rights movement in the USA. I saw racist Southern people who were victims of circumstance and would say positive things about white supremacy. I never dreamed I would live to see a time when people would again dare to say something positive about white supremacy. God help us! We can’t go backward; I won’t go backward. The founder of Christianity would not have us go backward.

Critical Race Theory: What is it?

I cannot believe the confusion that has come forth over Critical Race Theory. In the first place, why the educational elites would call this by this title is a total enigma. Like the comedian Steve Martin, when somebody made fun of his nose, I can create scores of better titles. First of all, I would never, ever, use the word “theory.” It has a ring of non-authentic drivel from educational elites. Why make it difficult? I would never use the word “critical,” which, in the South, immediately triggers the word “criticizing.” This brings natural negativity. What one word brings more immediate negative responses than the word “race?”

O.K. Blowhard Cloer, let’s hear some alternatives. “How many you want?” Like Steve Martin, I’ll present enough to prove my point, but not enough to bore you. That was always my first goal as a teacher and professor. (Under no circumstances should a teacher or professor bore students. It is the unforgivable sin in pedagogy.) Instead of “Critical Race Theory,” let’s call it “Improving Democracy as We Advance,” or “Looking for a Better Democracy.” Here are some obvious substitutions: “Advancing America’s Democracy,” or “Improvement as We Advance our Democracy,” or “Seeking Ways to Better our Democracy.”

Here is the substance of Critical Race Theory: Our American institutions have been affected historically by dividing the races. Prejudicial stratification, where one race is more entitled than another, led to the cancer of racism. This embedded, metastasized cancer is then made manifest at a later time in some of our American institutions. One that I am most familiar with, since I observed it so closely, was in our educational institutions. Most are familiar with the embedded problems seen so frequently of late in America’s criminal justice system. Others have studied and brought to the attention of America the disparities in our health care systems. Racism is a cancer that metastasizes and embeds deeply into a nation’s most important organs. I will give two very clear examples.

Educational Example

I began my educational career in the 1960s. I first went to school with African-Americans at Clemson. I was a student there when Clemson integrated its football team.

I began my educational career in the 1960s. I first went to school with African-Americans at Clemson. I was a student there when Clemson integrated its football team.

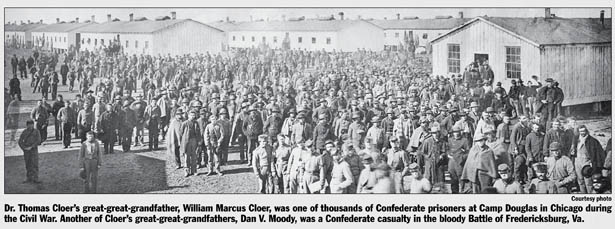

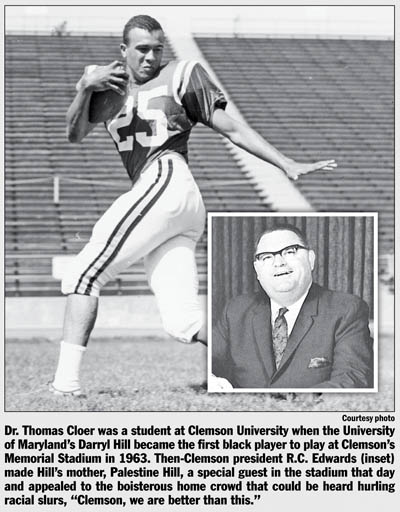

It was an ugly scene when the first African-American played in Clemson’s stadium. This was just before Clemson integrated its football team. Darryl Hill was the first black player to play in Clemson’s Memorial Stadium. Can you imagine the atmosphere when every school in every southern conference was segregated? Hill was an unbelievable pass receiver for the University of Maryland. His mother, Palestine Hill, was his greatest fan. When she arrived at Clemson’s football stadium, she was denied admission. The progressive Dr. R.C. Edwards was the president of Clemson when I was enrolled and was president when Palestine was denied admission. He was at the game and immediately made it very clear that Palestine was to be his most special guest to sit with him and his family in the president’s box.

Unfortunately, this did not deter the boisterous crowd that day. Racial slurs were heard throughout the stadium. Edwards was the man for the hour. He went to the center of the field and demanded the attention of the crowd. He so very eloquently appealed to the crowd’s better angels. “Clemson, we are better than this; I know we are.” Know what? He was right! The game proceeded, and Hill set records in receptions that stood for 30 years. Dr. Edwards’ “chemotherapy” arrested the boisterous crowd, and Clemson was on its way to “remission.” I am thankful that I was alive when this advancement in our democracy occurred.

The first African-American to play for Clemson was Marion Reeves, a defensive back. He played cornerback beside one of the best friends I ever had, Bobby Johnson, who later became football coach at Furman University. Coach Bobby Johnson took Furman to the national championship.

Metastasized Racism in

the Criminal Justice System

At one point in my career, I observed firsthand one of the most pathetic and poignant acts of discrimination that I have personally encountered in the criminal justice system. It has affected me to this day. For total anonymity, I will avoid all names and places.

A public defender called me from a county and asked me if I would consider giving diagnostic information to a court of law about a certain individual that he was trying to help. I said. “I’m interested; tell me more.” He then proceeded to ask me several questions. He said, “I’ve been told you have the credentials to testify in court and help me with a case. If a judge asks ‘What are his credentials?’ What should I say?”

I replied, “I have a PhD. in reading with an aligned field of psychology.”

“Dr. Cloer, can you determine a person’s reading level?”

“Yes,” I replied.

“Can you determine what level of reading ability a passage of text would require in order to read and understand?”

“There are several readability formulas in the professional literature that I use regularly for such purposes,” I replied.

He went on to tell me what the situation was.

“I have a poor black lady who is raising several young children. She was accused of signing a passage of text that she was supposed to have read and agreed to follow. Dr. Cloer, I really don’t know if she could have possibly read it. It supposedly required her not to work if she was receiving any welfare. She took a job cleaning, made a pitifully small amount of money, and was arrested. She is going to prison if found guilty. Can you help me?”

I wish I could forget the pitiful, pretty little black lady wearing an old tattered black sweater and carrying a little pink pocketbook. I was touched emotionally, because she was frightened. I calmed her fears and helped her relax.

Diagnosis, Findings and Conclusion

My head professor in my doctoral program was a renowned scholar, author and psychologist from Cornell University. He had researched and published extensively on the relationship of reading and listening abilities. His findings, which have stood the test of time, were that one can simplify the process of determining a person’s possible reading potential by comparing reading ability to that person’s listening ability. In other words, one should be able to read (if words are recognized) what one can listen to and understand.

The little lady worked diligently and showed clearly she was reading on a first-grade level. When I tested her listening ability using a well-developed instrument, she was also listening on a first-grade level. When I analyzed the written passage she had supposedly read, it was on a college graduate-school level. There was absolutely no way the little lady could have read and understood what she had signed.

I had done some similar work with the National Kidney Foundation. The foundation was having grave difficulty with South Carolinians reading and trying to follow written recommendations about diet. When I analyzed the difficulty of the written instructions, they were written on college graduate level by brilliant writers. The reading levels of those with kidney disease were elementary level. Since the outcome was life or death, I made a few simple suggestions. I suggested “Eat this” at the top of the recommended foods. I suggested they write “Do not eat this” at the top of the forbidden foods. I also suggested they put pictures with a check mark on each recommended diet picture, and a red “X” on each forbidden food. Understanding really is critical in some contexts.

In Court

I was about to get the shock of my life. Before my appearance in the court, the public defender shook my senses when he said, “Dr. Cloer, this is a case where the system wants to make an example of what happens when welfare is abused. This poor black lady is expected to be slammed, but I hope your testimony might reduce her sentence.”

I must say that I am embarrassed that I was so naïve. What I encountered shook my senses. It has forever challenged my perspective of justice being blind. When I began my statement, I told who I was and what my credentials were. I reported that the little lady whom I saw was reading and listening at a first-grade level, and the statement that she signed was written on a college graduate level.

“Whoa! Wait a minute here! Get the jury out of the courtroom!” the judge called.

The jury was escorted out. The judge then asked me a question that totally jarred my brain.

“How much are you being paid to come here and appear as an expert?”

I actually thought for a minute it must be a feeble attempt at humor. I answered, “Much less than I’m worth, Your Honor.”

I expected at least a smile from the judge; one was not forthcoming. Instead, I was about to be educated about being a very poor, lower-class black lady in our criminal justice system.

“Listen here!” the judge admonished. “I don’t like for someone to come in here and say that a person is retarded!”

I was appalled! I have never used that word! I began to see, however, that an attempt was being made toward a particular verdict.

It got much worse.

“I know all about you,” he said to me. “I even have one of your books here.”

He held up one of my books.

“I also hear you’re fond of running through swamps from the game wardens!”

He was referring to a situation when my then young son was duck hunting with me and his grandfather. It was a simple case of mistaken identity. Someone had been shooting over bait placed far away in a lake. We had never put out bait. We were not anywhere close to a lake. My family and I were completely exonerated.

The judge then looked at the little lady and called out very loudly, “You know right from wrong, don’t you? You know what happens down there on —- Street on Saturday night; don’t you? This is not about being unable to read or understand something!”

I was beside myself with cognitive dissonance. How could such a thing be happening? The jury was brought back in, and I finished my testimony before quickly getting the heck out of Dodge.

The Verdict

Later, I received a call from the public defender. “Dr. Cloer! You did it! We got a reduced sentence! I was very pleased with what we accomplished! Without your testimony, she would have spent a longer time in prison. She will probably get out now in ——.”

I was so shaken, I can’t remember what he said!

“What?? For God’s sake, who will take care of the children?” I asked.

“Now remember, Dr. Cloer, she was to be used as an example. I am absolutely happy with our result,” he said.

I was barely able to respond! I finally pulled myself together enough to say the following in closing our discussion.

“I didn’t know until now that, because of racism, sometimes a criminal justice system may be similar to professional wrestling. The outcome may be known before the bout!”

I then remember how gracious the public defender was, even after my comparison. I, however, felt as if I had just fallen from a turnip truck.

About the author: Dr. Cloer’s name is attached to an endowed scholarship in the Philosophy Department at Furman University by a thankful family “In appreciation for the guidance and concern for Furman Students.” He was the first South Carolina Governor’s Professor of the Year, chosen by the late Republican Gov. Carroll Campbell and his office, and the South Carolina Commission on Higher Education.